Space Marks

| Venue: | acb Attachment |

| Date: | Jan 14 – Feb 18, 2022 |

| Opening: | Jan 13, 2022, 18:00 |

Description

Exhibiting artists: Imre Bak, Burda Krystian, Ferenc Ficzek, Károly Hopp-Halász, Károly Kismányoky, Sándor Pinczehelyi, Kálmán Szijártó

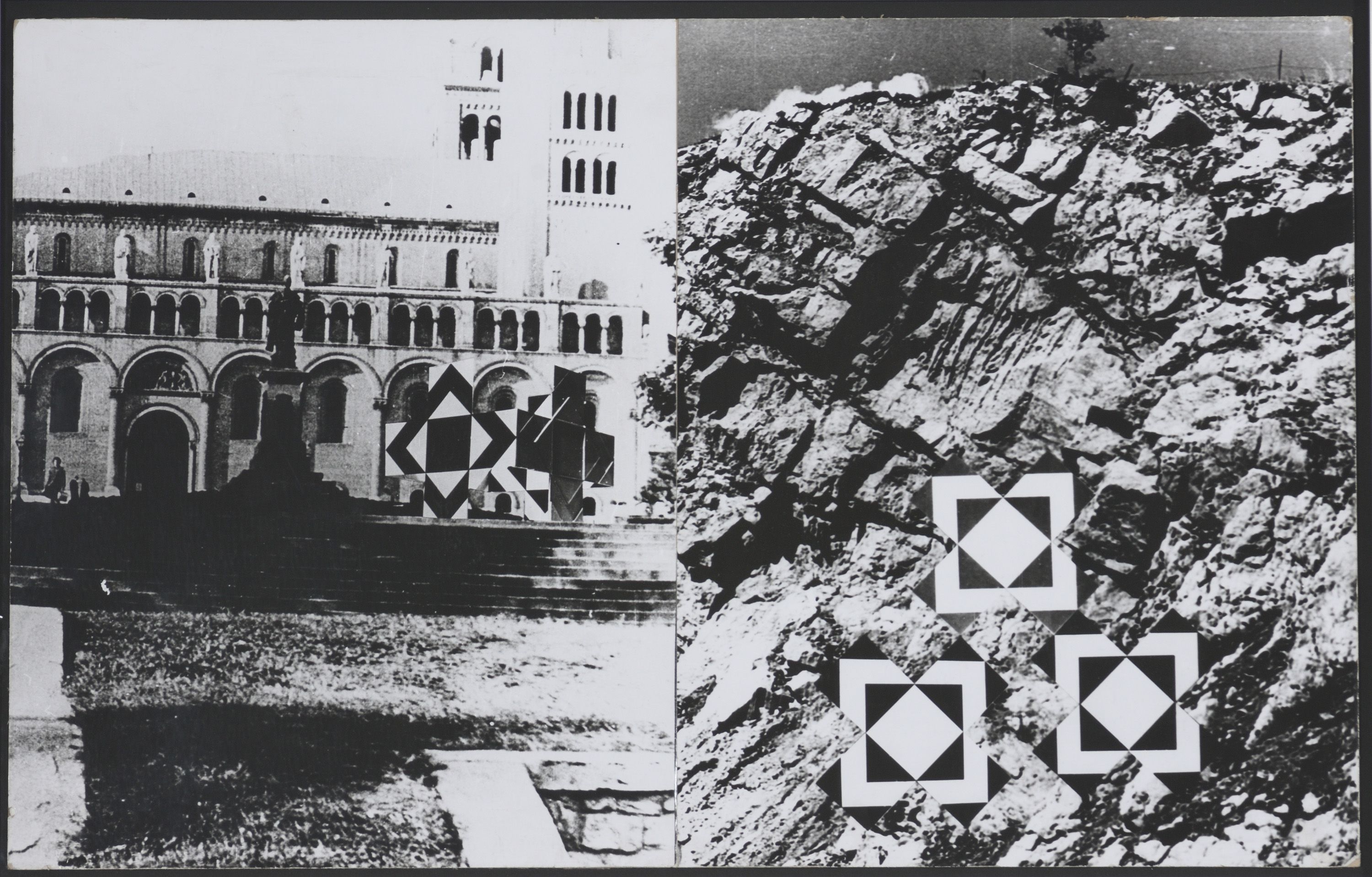

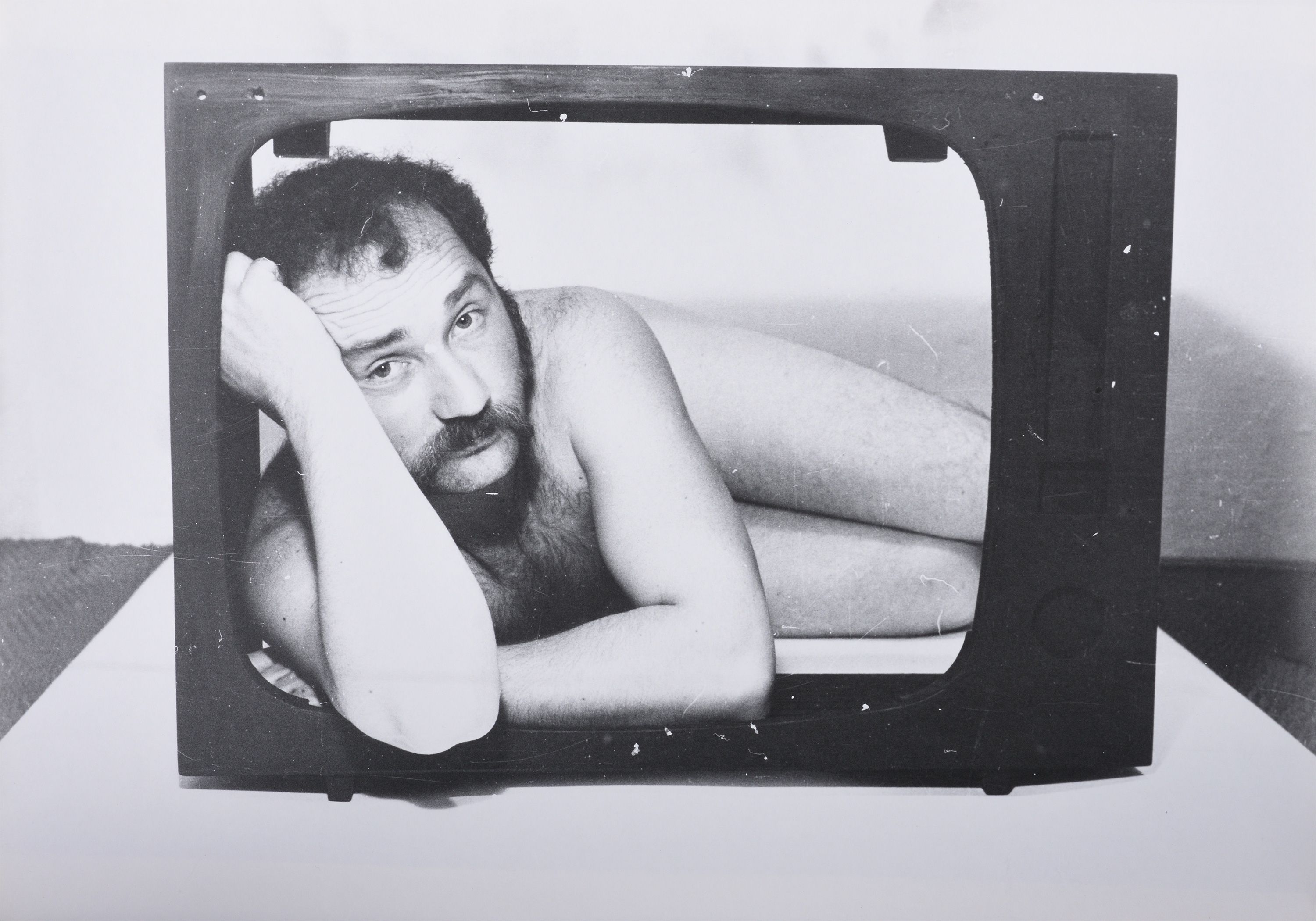

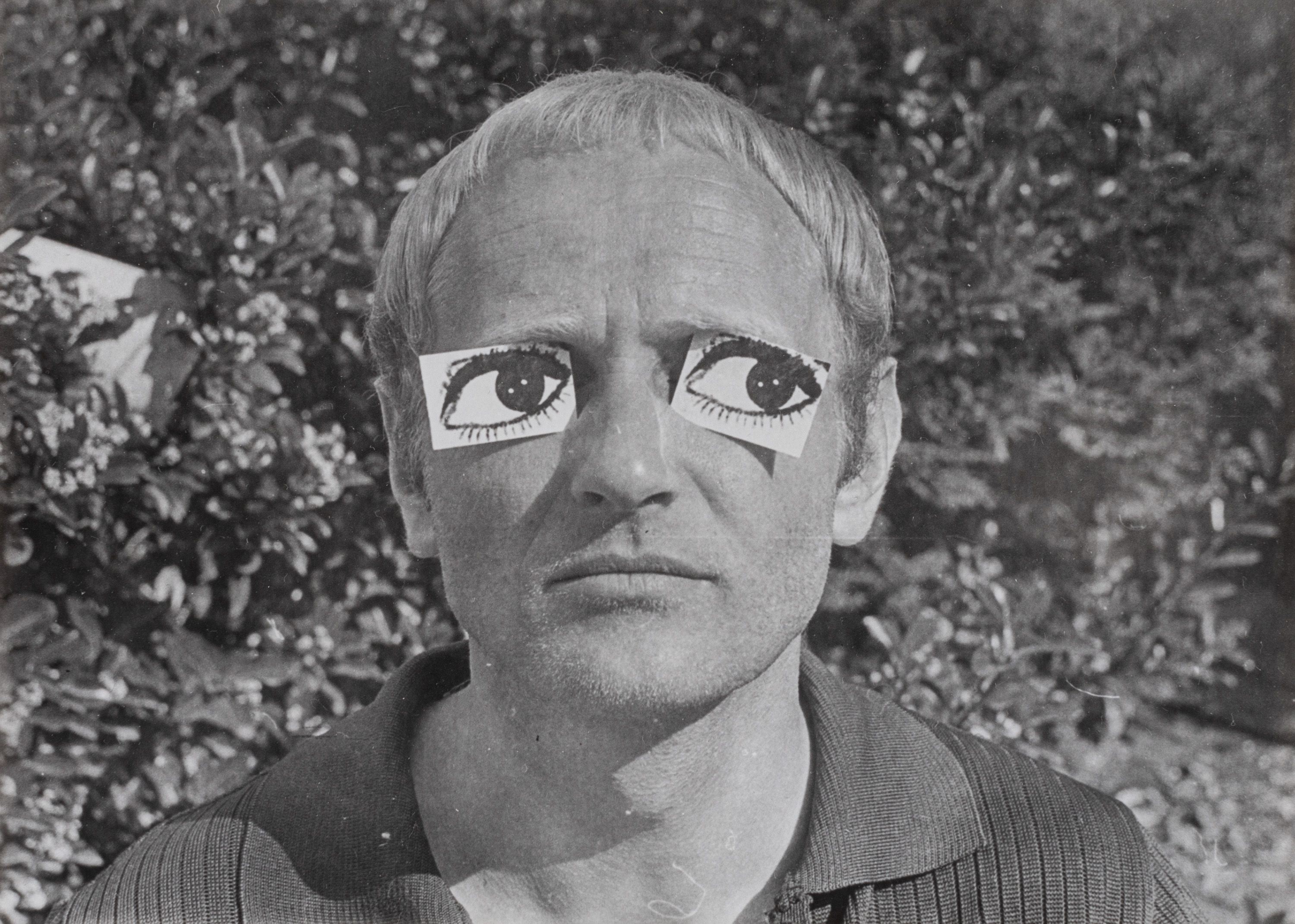

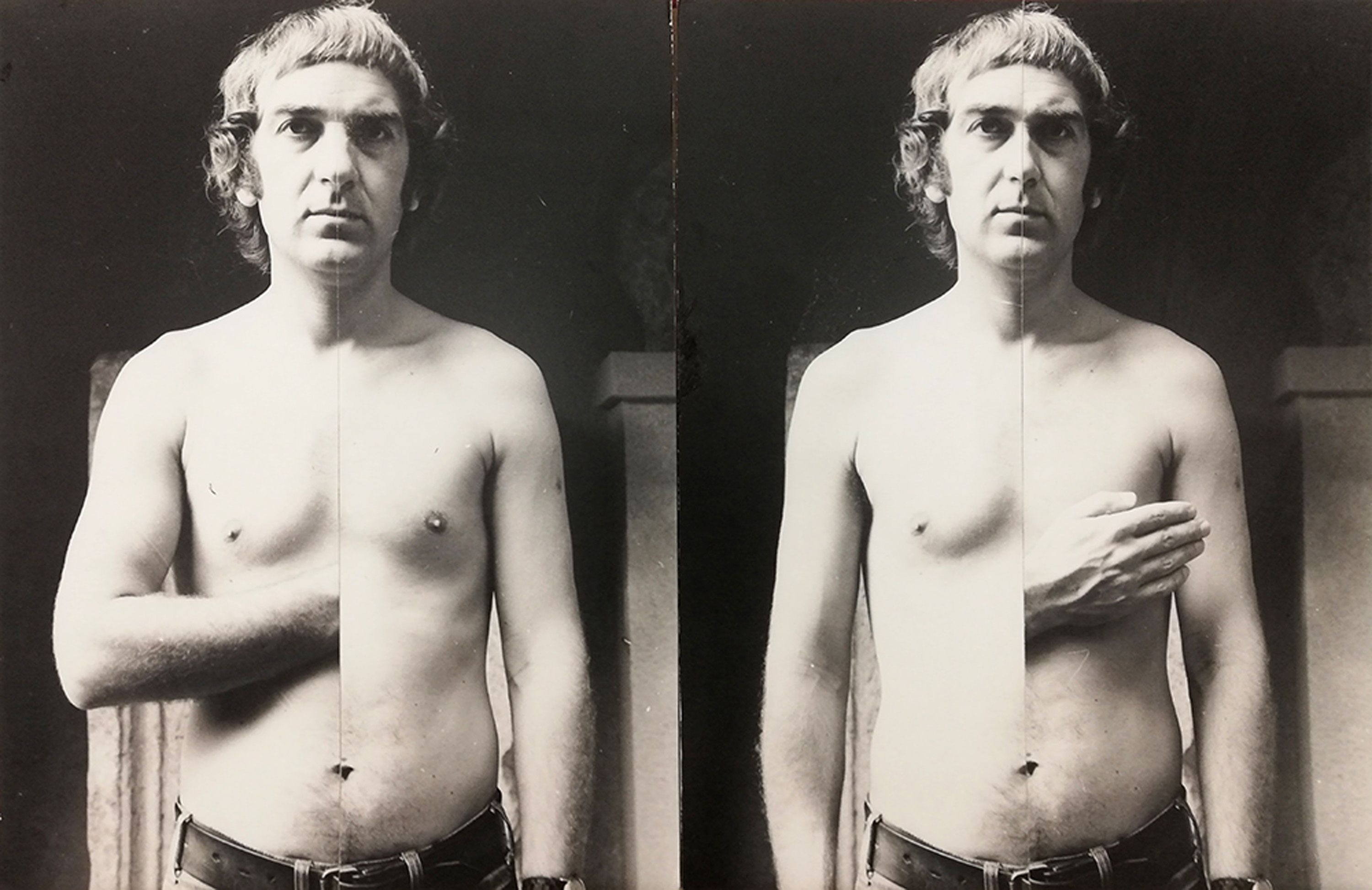

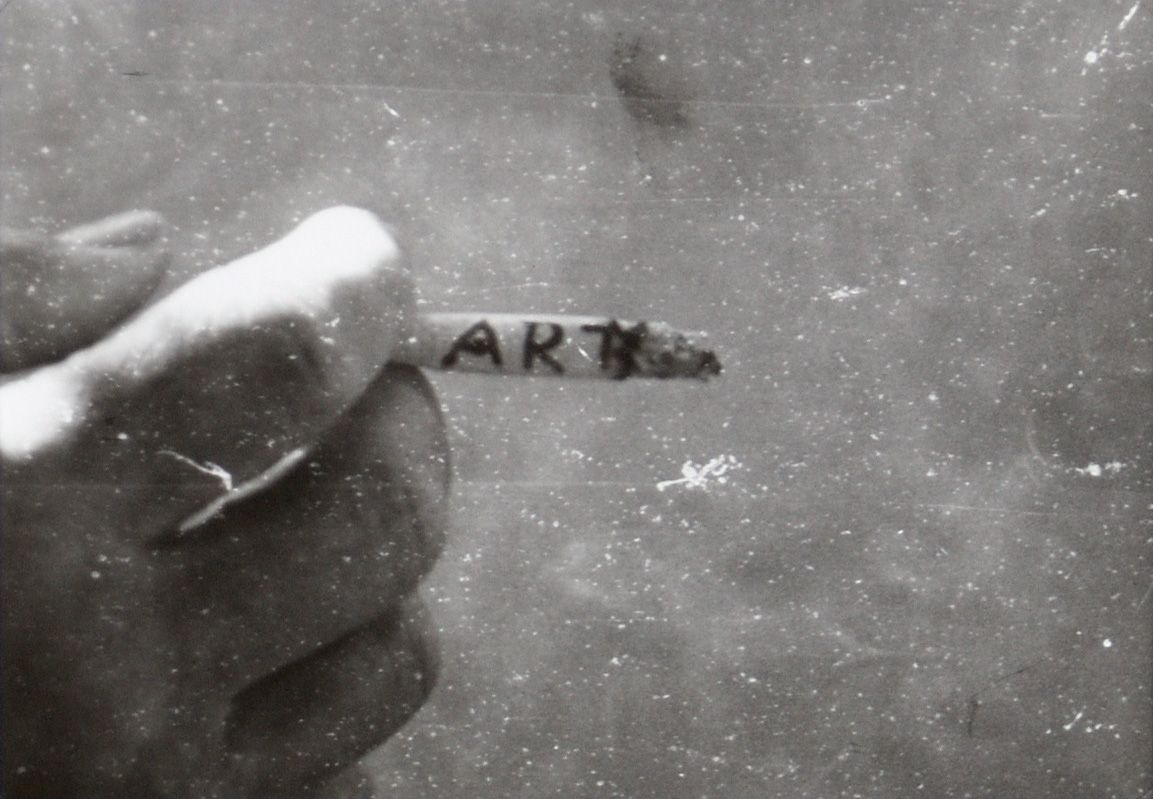

In recent years, much attention has been directed to the art experiments that took place at the Bonyhád Enamel Factory during the late sixties and early seventies. These activities, initiated by Kamill Major and later Ferenc Lantos, took shape in 1968 as the “Architectural Enamel Art Camp” with the participation of Gyula Pauer, Tihamér Gyarmathy and Oszkár Papp. From 1969 to 1972, members of the Pécs Workshop – which had formed from a group of Lantos’s students (Ferenc Ficzek, Károly Hopp-Halász, Károly Kismányoky, Sándor Pinczehelyi, Kálmán Szijártó, and initially Lajos Szelényi) – regularly attended the art camp in Bonyhád (then, from 1970 onwards, in Mecseknádasd). In 1970 and 1972, the list of participants, among others, came to also include such representatives of geometric abstract art as Imre Bak and János Fajó. In interpreting the events that occurred at Bonyhád, significant insights have been gained not only from the shows and publications of the acb Gallery and its exhibition projects in cooperation with the Vasarely Museum and the Janus Pannonius Museum, but also from the exhibitions entitled Separate Ways – Karl-Heinz Adler and Hungarian Abstraction (Kiscelli Museum/Kassák Museum, 2017), and 1971– Parallel Nonsynchronism (Kiscelli Museum, 2018/9). By bringing to the fore the considerations and international aspects that emerged during the memorable "abstraction debate" of the 1960s, these exhibtions have helped outline the context in which linking fine arts with architecture and industry offered abstract art an alternative, and also – in the form of mural works of art – the opportunity to benefit from more permissive climate of cultural policy. The research exhibition presented at acb Attachment – as the first stage of a research project supported by the Visegrád Fund – through an interview video created for the show, seeks to nuance the relationship between the Hungarian symposium movement (which began in 1968 and reached its heyday in the 1970s) and the art activities that took place at the Bonyhád Enamel Factory. At the same time, the exhibition is also connected to the history of how these activities at the Bonyhád Factory (relating not only to enamel art) appeared on the avantgarde platforms of the era, thereby outlining the intersection of these two domains. The works on display are selected from the material – conceived mainly in the spirit of geometric abstraction – that members of the former Pécs Workshop (with the exception of Károly Hopp-Halász) submitted in response to a call for works announced in 1971 by art historian László Beke under the title The Artwork = the Documentation of the Idea. Imagination/Idea, which is regarded as the first collection of Hungarian conceptual art, sheds light on some heterogeneous interpretations of the relationship between art and ideas, based on the works of the artists whom Beke sought out in the early seventies. In including enamel works and enamel designs tied to the activities in Bonyhád, the material submitted by the Pécs group – as pointed out by Róna Kopeczky, László Százados and Zsóka Leposa – introduced into this collection a kind of functional, but also dynamic, thinking about public space and the natural environment, based on considerations that were modernist but also urbanistic, as inspired by Vasarely’s work. In addition to the variability and seriality inherent in enamel art, its categorisability as applied art also played a particularly important role in this respect. This point is evidenced not only by Lantos’s letter submitted in response to the call, but also by Sándor Pinczehelyi’s semiotics-inspired montages, which question the traditions of commemorative monument building. Ferenc Ficzek’s cube addresses the problem of creating and perceiving space, while also bearing traces of Gyula Pauer’s pseudo and Vasarely’s method built on illusory effects. The work, which was included in the Imagination/Idea material only in the form of a “draft”, can also be brought in connection with this thought, while Ficzek’s spray-painted “imprints” are based on found objects. The chain of thought that connects the initial planning stages of the artwork with experiments in form and medial variations, and, then, with the execution phase, can clearly be traced in the documents entered by Kálmán Szijártó and Károly Kismányoky, a selection of which is presented at the exhibition. The rhythm of their joint land art actions – which were closely related to the artists’ stay in Bonyhád, also bringing to the foreground the ties created between geometric forms and the natural environment – and the element of the paper ribbons woven through the trees and the landscape are also echoed in Kismányoky’s enamel art. Taken together, these reflect back the interconnections between the varied forms arising from the different motifs, genres, techniques, and conceptualisations of space.

The exhibition is complemented by the screening of an experimental student film shot in 1961 in the Sculpture Department of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw by a recently discovered artist of Central European modernism: Polish designer and visual artist Krystian Burda (1935-2015). Burda's oeuvre is linked in multiple ways to ideas formulated by Hungarian artists about public space, landscape interventions, process art, neo-constructivism, as well as works both realised and unrealised, in a space defined by the social and aesthetic intentions of the socialist industry. The film comprised part of Burda’s degree work – which, in its day, created quite a stir and then quickly became legendary – involving the design of a Chopin monument. The 10-kilometre-long monument envisioned by the artist, which he planned to erect along the road leading to the Polish composer’s house of birth, was to employ solutions that were unusual for the period in terms of both form and memory politics. The work – which, building on the sculptural and temporal effects created by the interplay between piano keys and landscape elements, was to be “activated” by the viewer’s movements – remained a modernist study of space, an idea. Burda’s experimental film (camera work by Andrzej J. Wróblewski), originally used as a visual demonstration tool for presenting the concept of the yet unrealised artwork – in addition to a mockup of the monument, photos of the landscape surrounding the road, and a rotating relief (reminiscent of solutions seen in Yaacov Agam’s proto-op art sculptures) modelling the thought process behind the idea – became his degree thesis. This work, made during the era of de-Stalinisation or the “Polish Thaw” with its increased permissiveness towards abstract art, in addition to showing close ties to Burda’s teacher, internationally renowned architect Oskar Hansen and the “open form” concept he promoted, also attests to a strong connection not only to the traditions of Polish constructivism, but also to Vasarley’s art, which served as a source of major influence to the Pécs artists as well. Burda’s work can be counted among those which paved the way for such events as the international symposium movement – which, called to life by Austrian artist Karl Prantl, also provided networking opportunities to artists living and working behind the Iron Curtain – as well as the conventions and exhibitions organised under the auspices of the so called Polish Plein Air (plener) network. Further examples include the Biennial of Spatial Forms in Elbląg, a large scale event that rethought the possibilities of public art from the perspective of the constructivist traditions (the first of which, held in 1965, was also attended by Tihamér Gyarmathy), the Puławy Symposium, which – in the spirit of the originally propagandistic linking of art, industry and science – took place at the Chemical Plant, or the Wrocław’70 Symposium. Similarly to the situation in Hungary, the organisation of these factory-related conventions were made possible by the political agenda which, in aiming to bring representatives of the fine arts and socialist industry closer together, contributed to the reshaping of cityscapes after the war, while also creating opportunities for progressive tendencies. Burda did not participate in these events, although he later worked as an industrial designer himself, bringing his systematic, rational and modernist approach to design. For over thirty years, he worked as a designer of household articles, enamel utensils and objects, murals, and interiors at the Rybnik Ironworks, while also producing his autonomous works, using steel and enamel to create non-figurative panel paintings, reliefs and small sculptures in his workshop. From the early 1970s, he designed numerous enamel murals throughout Silesia, Poland and the former Czechoslovakia, including the facade of the now destroyed Diamant department store (Wodzisław Śląski) – a work that utilised the decorative and variational possibilities of enamel art.

We owe our thanks to Imre Bak, Sándor Pinczehelyi, László Százados, Fundacja Polskiej Sztuki Nowoczesnej, Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej ̶ BWA Katowice, Małgorzata Kaźmierczak, Iwona Demko, Karina Dzieweczyńska (Centrum Sztuki Galeria EL, Elbląg) and Bernadeta Stano for their help.

Space Marks - Sándor Pinczehelyi, Imre Bak

video 41’55”, acb, 2022

Camera: Benedek Bognár

Editing: Bendek Bognár, Zsuzsanna Simon

Concept, script: Kata Balázs

Translation: Zsófia Rudnay

The project is co-funded by the governments of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia through a grant from the International Visegrád Fund. The Fund's mission is to promote sustainable regional cooperation in Central Europe.