Vasarely's Ceramic Utopia

In its latest article, acb ResearchLab features Márton Orosz, the director of the Vasarely Museum Budapest, who writes about the unique collaboration between the world-famous Hungarian-born artist Victor Vasarely and the German Rosenthal company. The publication coincides with acb Gallery’s first international fair participation this year. Between January 22 and 26, our gallery will take part in the prestigious ceramic brussels 2025 ceramics fair, where, at our historically-focused booth, (alongside works by László Borsódy, Lajos Csertő, and Judit Vida) Vasarely’s op-art ceramic reliefs will also be on display, which the artist designed for the façade of the Rosenthal store in Paris.

Philipp Rosenthal, founder of the Rosenthal company, identified the demand for painted porcelain—often referred to as “white gold”—while establishing himself as an entrepreneur in the United States. Upon his return, he established the company as a family-run manufactory in Selb, Bavaria, in 1879, focusing on producing porcelain items and household goods. Within 25 years of its establishment, the company became one of Germany’s leading porcelain manufacturers, employing nearly 1,500 workers. However, it was closed in 1945 following the Second World War and was not revived until 1951. Beginning in 1952, Philipp Rosenthal’s son, Philip Rosenthal, joined the company’s design department at the Selb factory. Philip, a graduate of the University of Oxford where he studied philosophy, political theory, and economics, assumed the product manager role in 1964. In 1959, Philip Rosenthal met Arnold Bode, the art historian and founder of documenta, during the second edition of the renowned international contemporary art exhibition held in Kassel, which occurs every five years. This meeting inspired the idea of commissioning contemporary artists—who had never previously worked with ceramics—to design works for Rosenthal’s porcelain line.

In 1961, Arnold Bode was appointed to Rosenthal’s seven-member international product development council. He suggested that the 1964 documenta III exhibition, centered on the theme “Pictures in Space – Art and Urbanism” and conceived as a “museum open for 100 days,” should include works by artists such as Étienne Hajdu, Ben Nicholson, Lucio Fontana, Günther Uecker, and Victor Vasarely. These artists’ works were to be reproduced as limited-edition porcelain objects and sold through the documenta Foundation.

Rosenthal’s participation in the 1964 documenta significantly enhanced its position as a globally influential representative of the porcelain industry. Between 1965 and 1969, the company constructed a new porcelain factory in Rothbühl, designed by Walter Gropius, the founding director of the Bauhaus school. This industrial facility, which became an iconic work in Gropius’s later career, features a rainbow mural by the Zero-artist Otto Piene. The wall painting is reminiscent of the work he created for the opening ceremony of the 1972 Munich Olympic Games—whose logo was designed by Vasarely himself—which incorporated balloons to create a “Sky Art Installation.”

At the subsequent documenta IV held in 1968, Arnold Bode presented multiples in a dedicated section under the title “Edition 68,” making the reproduced works available for purchase as part of the “Ambiente” project. While screen prints were the main focus of this exhibition, Bode sought to highlight porcelain works specifically. Following the Kassel event, in September 1968, he organized the “Ars porcellana” exhibition at the Kunstverein in Cologne. This exhibit showcased the works of artists such as Victor Vasarely, Salvador Dalí, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Nikki de Saint Phalle, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, Max Bill, Jean Cocteau, and Otto Piene. In total, 33 ceramic pieces by 23 artists were displayed, collectively known as the “Rosenthal Relief Series,” which had been produced at the Selb factory between 1964 and 1968 in limited editions of 6 to 100 pieces.

The concept of reproducible art was not entirely unfamiliar in Cologne. Between 1959 and 1960, Daniel Spoerri, in collaboration with Galerie Spiegel, introduced the Edition MAT (Multiplication d’Art Transformable) series, featuring works also by Victor Vasarely, along with Marcel Duchamp, Josef Albers, Pol Bury, Bruno Munari, Dieter Roth, Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely. This initiative aimed to democratize art by making it available in multiple editions. However, Rosenthal’s 1968 Cologne exhibition received a poor reception. Apart from Lucio Fontana’s works, a few pieces were sold. This failure was attributed to Bode’s emphasis on the reproducibility of the works and his attempt to redefine the concept of multiples as a new aesthetic category, which was met with public resistance. For instance, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung noted that Vasarely’s porcelain pieces were priced at 12,000 Deutsche Marks each—prohibitively expensive for most collectors at the time. Additionally, the production limitations of the porcelain pieces hindered the feasibility of creating large editions. The negative molds used in the Selb factory were designed for a maximum of 10–25 reproductions, making the production of large series time-consuming and costly, ultimately jeopardizing the project’s profitability.

The setback of the Cologne exhibition was not the only reason Philip Rosenthal and Arnold Bode parted ways. A more serious issue arose when it was discovered that Bode had misappropriated funds during the sale of the multiples, leading to a police investigation. Following Bode’s departure, Philip Rosenthal appointed Eugen Gomringer, a Bolivian-born Swiss concrete artist and curator who had been advising the company since 1966, as the new artistic consultant. One of Gomringer’s first initiatives was to commission Salvador Dalí to collaborate with Rosenthal. He also conceptualized the limited-edition “Rosenthal Studio-Line” collection, featuring notable contemporary artists such as Helmut Andreas Paul Grieshaber, Eduardo Paolozzi, Ivan Rabuzin, Victor Vasarely, Björn Wiinblad, and Rut Bryk. His original vision aimed to involve 100 artists in creating an exclusive series for Rosenthal. To further promote contemporary porcelain art, Gomringer suggested the establishment of dedicated Rosenthal galleries in Munich and Cologne. He also organized travelling exhibitions of Rosenthal’s unique porcelain works, supported by loyal international patrons, in countries such as Canada, Italy, the United Kingdom, Czechoslovakia, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland. These exhibitions significantly boosted the popularity and prestige of the Rosenthal brand.

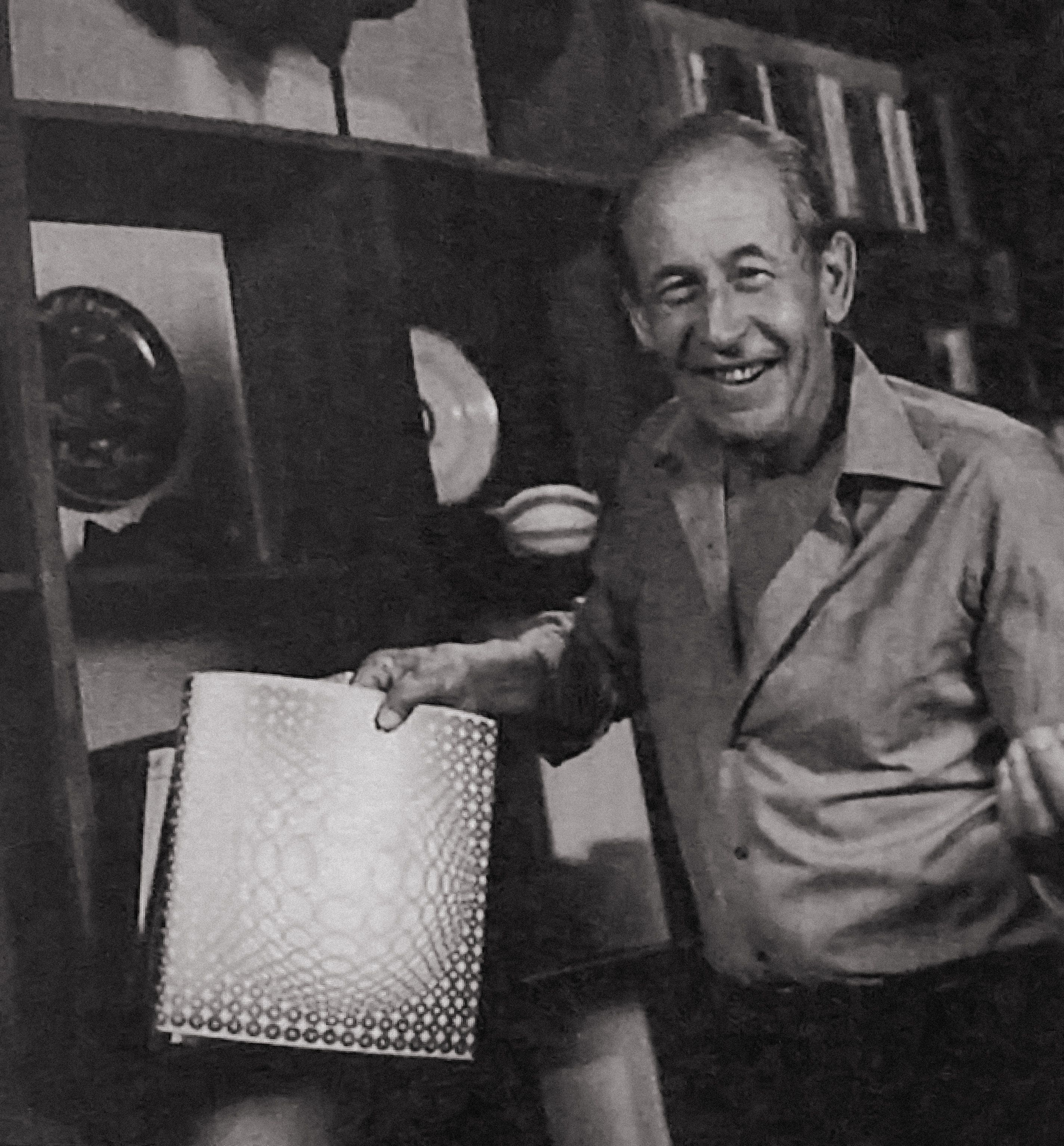

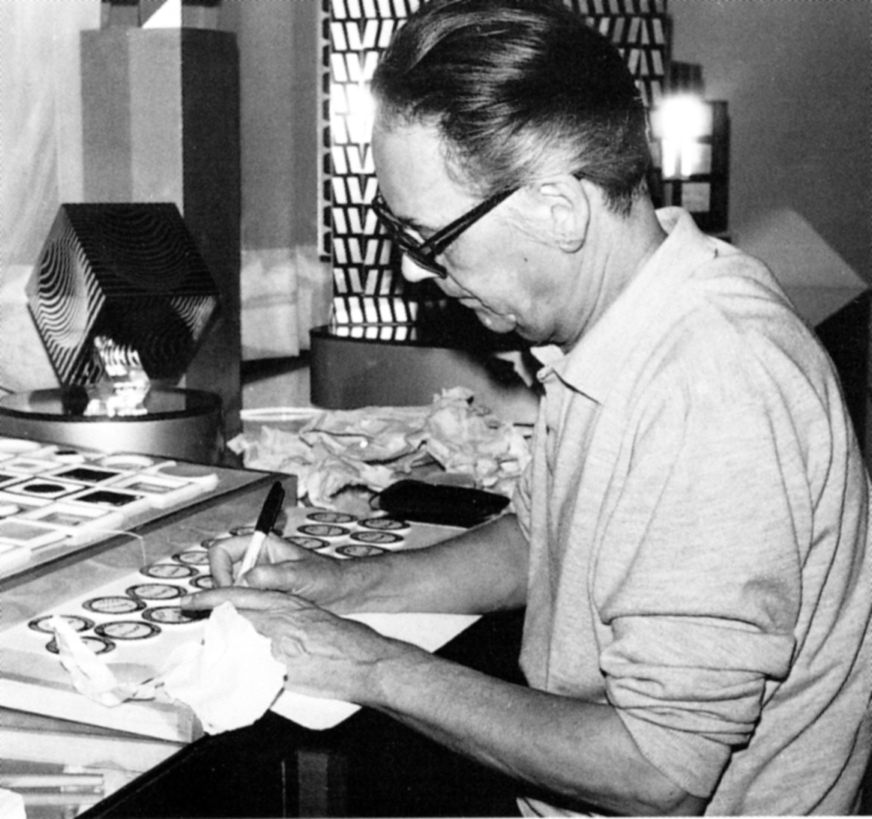

Victor Vasarely’s collaboration with Rosenthal began in 1964 and continued closely until 1988, with his designs being produced in various editions until 1997. This partnership provided Vasarely the opportunity to express his artistic vision through a new medium—porcelain. During his collaboration with Rosenthal AG, the Hungarian-born artist created several limited-edition art collections, including the Laika, NB 11, NB 22 Canope, and Relief series, with production quantities ranging from 50 to 100 copies. The manufacturing of the NB 11 porcelain multiple was particularly challenging; the composition shrank significantly during the drying process, requiring 100 trials to finalize a workable casting solution. This difficulty prompted Vasarely to rethink his original concept, leading to a modular approach for the NB 22 Canope, which resulted in an impressive 2×2-meter composition. In 1971, Vasarely designed the Composition Carrée relief series for Rosenthal Studio-Line, consisting of 13 variations. These pieces featured aluminium frames, MDF bases, and stainless-steel screws for structural stability. Each of them was signed by Vasarely and accompanied by a numbered certificate label issued by Rosenthal.

During the 1970s, Vasarely expanded his work with Rosenthal, designing numerous other products, including the Manipur tea set (produced in an edition of 100), as well as vases, planters, glasses, and trays, some of which were produced in editions of 500. Certain items, such as the gold-glazed Duo tableware compositions, were released in extremely limited quantities. In 1977, the artist created an annual porcelain plate for collectors, known as the Jahresteller, and in 1978, he contributed to a new series of plates and decorations for Timo Sarpaneva’s Suomi porcelain design and various relief works. Rosenthal’s collaboration with the Zsolnay factory in Pécs during the 1970s also resulted in vases, tea sets, and reliefs, with production quantities ranging from 200 to 5,000. Throughout his partnership with Rosenthal, Vasarely designed nearly 90 porcelain objects between the late 1960s and early 1980s. This collaboration not only yielded limited-edition artworks but also promoted the integration of art and design into everyday life, highlighting Rosenthal’s innovative and progressive approach to contemporary art.

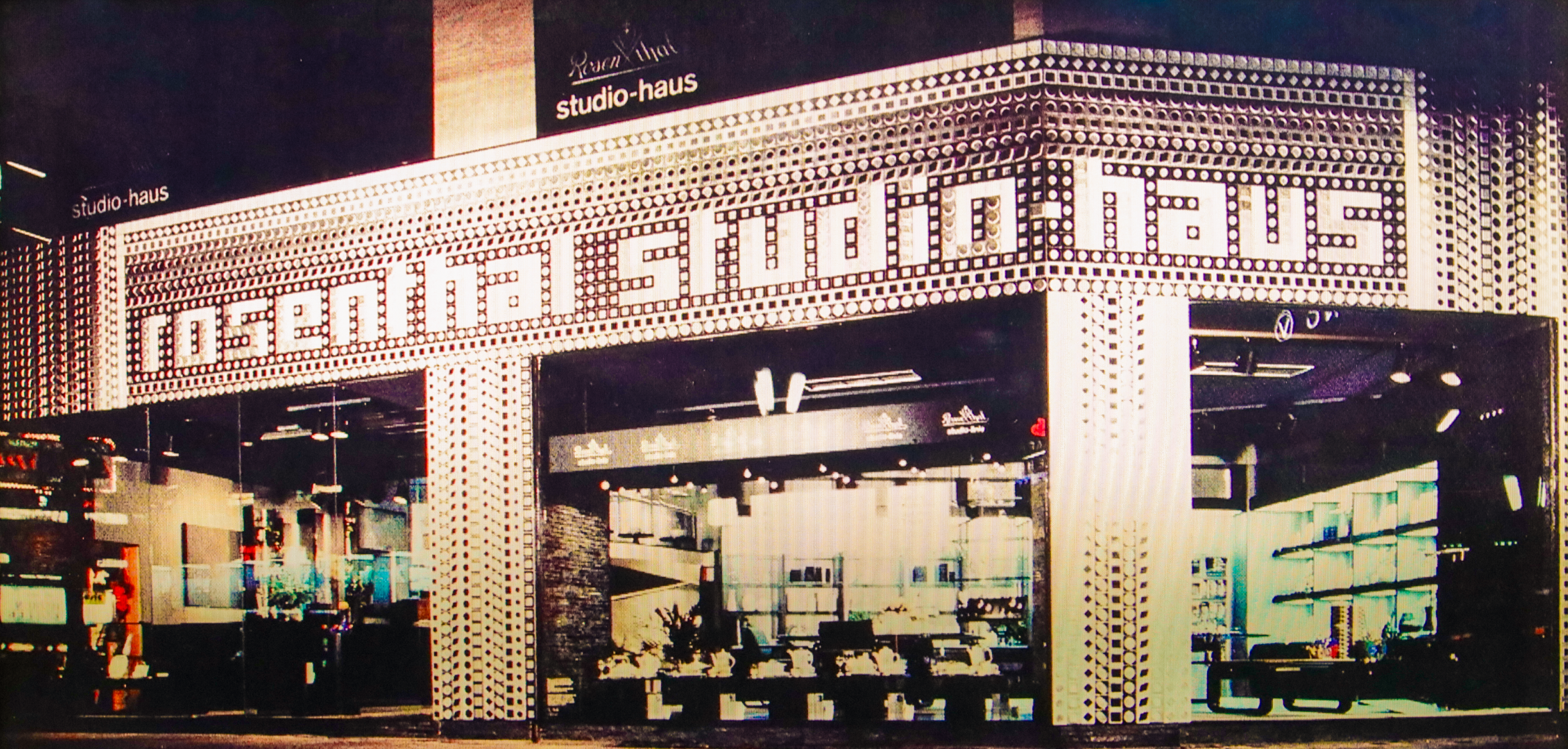

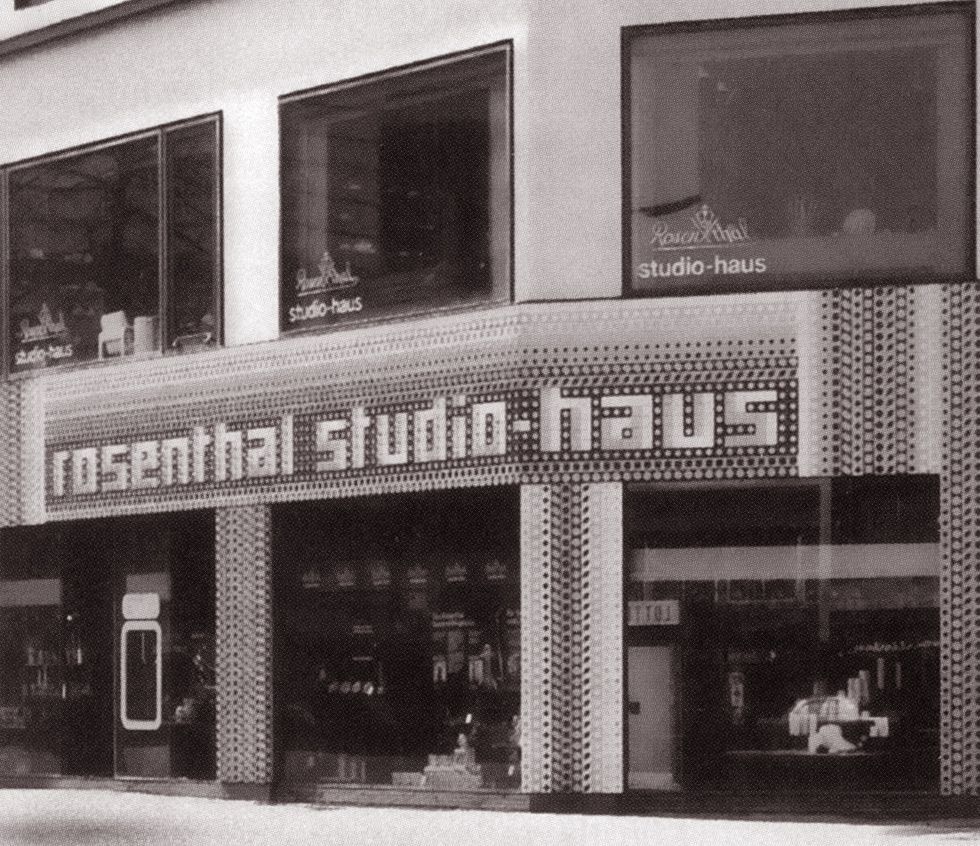

One of the most remarkable outcomes of the partnership between Victor Vasarely and Rosenthal was the decoration of Rosenthal Studio-House facades with variations of Vasarely’s NB compositions (the title indicating “noir-blanche,” or “black-and-white”). The concept of Rosenthal Studio-Houses emerged in the mid-1970s. Approximately 100 such stores were established worldwide, with around 35 located in West Germany. These stores combined showrooms and retail spaces for Rosenthal’s porcelain design products. The first Studio-House opened in Nuremberg in 1961, followed by locations in major German cities such as Kiel, Bremen, Hamburg, Bielefeld, Dortmund, Bochum, Essen, Düsseldorf, Bonn, Frankfurt, Mannheim, Stuttgart, Munich, Berlin, Hanover, and Wiesbaden. Düsseldorf had as many as three stores, though only one was in operation at a time. This explains why Vasarely’s facade was not featured on the first store (opened in 1963 on Königsallee), but was instead displayed on the second store two decades later. Beyond Germany, Rosenthal Studio-Houses were established in cities such as Stockholm, Copenhagen, Luxembourg, Brussels, Amsterdam, Zurich, Geneva, St. Gallen, Paris, Vienna, Milan, and Rome. These stores showcased and sold Rosenthal’s porcelain design products. Their facades varied in size based on the layout of each building’s entrance, but they maintained a consistent aesthetic to ensure brand identity. In Germany, for example, this approach echoed the uniform facades of the Horten department stores built in the 1960s, which distinguished them from conventional shopfronts and gave them a unique identity. Rosenthal adopted this concept, integrating Vasarely’s innovative designs into the Studio-House aesthetic, further strengthening its brand image and artistic prominence.

Philip Rosenthal commissioned Victor Vasarely to design the exterior of four unique buildings located in Berlin, Bonn, Düsseldorf, and Paris. The Berlin one was inaugurated in 1978, and composed of 3,965 modules. The Paris store’s facade, completed in 1979, consisted of 2,992 porcelain tiles. Similarly, the Bonn store, which opened in 1979, featured a cladding made from 3,206 porcelain elements. In Düsseldorf, the store with Vasarely’s relief facade was not unveiled until 1985. This was the city’s second Rosenthal store, located at Jan Wellem Platz, following the closure of the first shop. All these architectural designs that defined the store’s outward appearance, reflected the themes of “art in architecture” and “art in the city.” The modularity and structural elements of the facades, including circles, rhombuses, and squares, contributed to the cohesive aesthetic of the Studio-Houses. The reliefs, constructed from grids of 10×10, 7×7, and 6×6 units, varied in compositional structure across locations. The entrances of the stores were fully clad, from floor to roof, with Vasarely’s sculptural units—geometric combinations of circles, rhombuses, and squares in black and white. This design allowed for theoretically infinite permutations, emphasizing a sense of dynamism and modularity. Victor Vasarely’s facades featured structural frameworks made of metal, to which porcelain tiles were affixed. For instance, in Berlin, the modular elements measured 1 meter by 1 meter and consisted of 10 cm by 10 cm tiles (100 tiles per module) mounted onto a larger ceramic plate.

The interior designs of the Rosenthal Studio-Houses were equally innovative. Spread across two levels, the interiors employed minimalist elements in black, white, and gray tones, creating a stark and elegant contrast that highlighted the porcelain products on display. Each location incorporated unique architectural solutions. For instance, in Berlin, a ramp was added for the convenience of customers. The latter store’s facade became particularly noteworthy, with the German press heralding it as “the world’s largest porcelain relief” during its opening in 1978. The choice of location on Kurfürstendamm was made on Philip Rosenthal’s recommendation. The proximity to Café Fuchs, one of West Berlin’s most famous cafes at the time, was considered advantageous from a marketing perspective, adding to the commercial appeal of the Charlottenburg-based business.

The porcelain facades created for Rosenthal occupy a distinctive place in Victor Vasarely’s oeuvre. As site-specific, uniquely designed architectural integrations, they stand out as the only such works commissioned by a company specializing in design and the sale of reproduced artworks. These innovative projects exemplify the synthesis of art, architecture, and commerce, leaving a lasting legacy in both Vasarely’s career and Rosenthal’s corporate identity.

The Paris Studio-House was Rosenthal’s 31st such establishment. Founded in 1978 and opened to the public in 1979 on Boulevard des Capucines, the location operated until 1989. The Rosenthal Studio-House in the French capital spanned two levels and covered an area of 251 square meters, featuring unique interior design solutions. The display arrangements were meticulously designed to maximize the impact of material, form, and decoration. Presentation elements were rendered in black, white, and gray, avoiding any distinct architectural or decorative character to create a subtle but striking contrast that highlighted the porcelain objects on display. The spatial layout of the exhibits emphasized the relationship between material and form more dominantly than any previous presentation concepts.

Larger stores, such as those in Berlin and Hamburg, incorporated dedicated art galleries. The West Berlin Studio-House, in addition to porcelain, glassware, and cutlery, showcased Rosenthal’s furniture collections and featured a separate gallery space for limited art editions from the Rosenthal Studio Line. Notably, the Cologne Studio-House was the only Rosenthal establishment with a gallery that operated independently of the store itself. This one-of-a-kind setup was justified by the city’s popularity as a hub for art fairs, particularly the Kunstmesse. A distinctive feature of the Berlin store was its video program, which screened films about artists collaborating with Rosenthal, providing customers with insights into the processes of product development and manufacturing. Based on an interview I conducted with Eugen Gomringer, Studio-House stores employed trained hostesses with backgrounds in art history to refine customers’ tastes and escort them through the gallery area. This approach provided clients with multi-channel access to information about Rosenthal’s unique aesthetic philosophy. Another distinctive aspect of the Berlin store was its ramp, which replaced a conventional staircase leading to the upper level. This design decision enabled customers to ascend gradually and comfortably, catering to parents with strollers and elderly visitors, thereby improving accessibility and convenience.

Recollections from Alfons Müller and Wolfgang Fassbender, two former Rosenthal employees, highlight the enthusiasm with which both customers and staff received these facades. The personnel expressed pride in the artistic decorations adorning their stores, while customers were drawn to the unprecedented appeal of shopping in a space that prioritized design and fine art alongside commercial goals. This commitment to aesthetic innovation significantly contributed to the success of a new culinary culture grounded in refined design principles. The execution of Victor Vasarely’s designs for the facades of the Rosenthal Studio-Houses was created by the Rosenthal AG architectural department (“Rosenthal Bauabteilung,”) led at the time by architect Hans Weiß. The tiles were manufactured at the company’s factory in Selb, under the direction of Wilhelm Heublein.

The panels were affixed to ceramic slabs using a specialized adhesive. However, it should be noted that the ceramic-clad storefronts were not intended to be permanent installations. According to the terms of the leases for the Studio-Houses, all the facades had to be dismantled and the building exteriors restored to their original state upon the expiration of the lease agreements. Lease terms were tailored to the circumstances of each location and required flexibility to meet landlords’ expectations. As a result, investments in the building’s exteriors needed to be proportional to the duration of the lease agreements. Upon the termination of a lease or the closure of a store, the facades were demolished following contractual obligations. However, the leases did not specify what would become of the ceramic panels after their removal. Since Victor Vasarely was responsible only for the compositional designs, with Rosenthal handling the execution and installation of his works, he had no legal claim over the removed pieces. The lack of provisions regarding the disposal of Vasarely's NB reliefs after the facades were de-installed left their fate solely in the company’s control.