Endre Tót

Why Do I Paint?

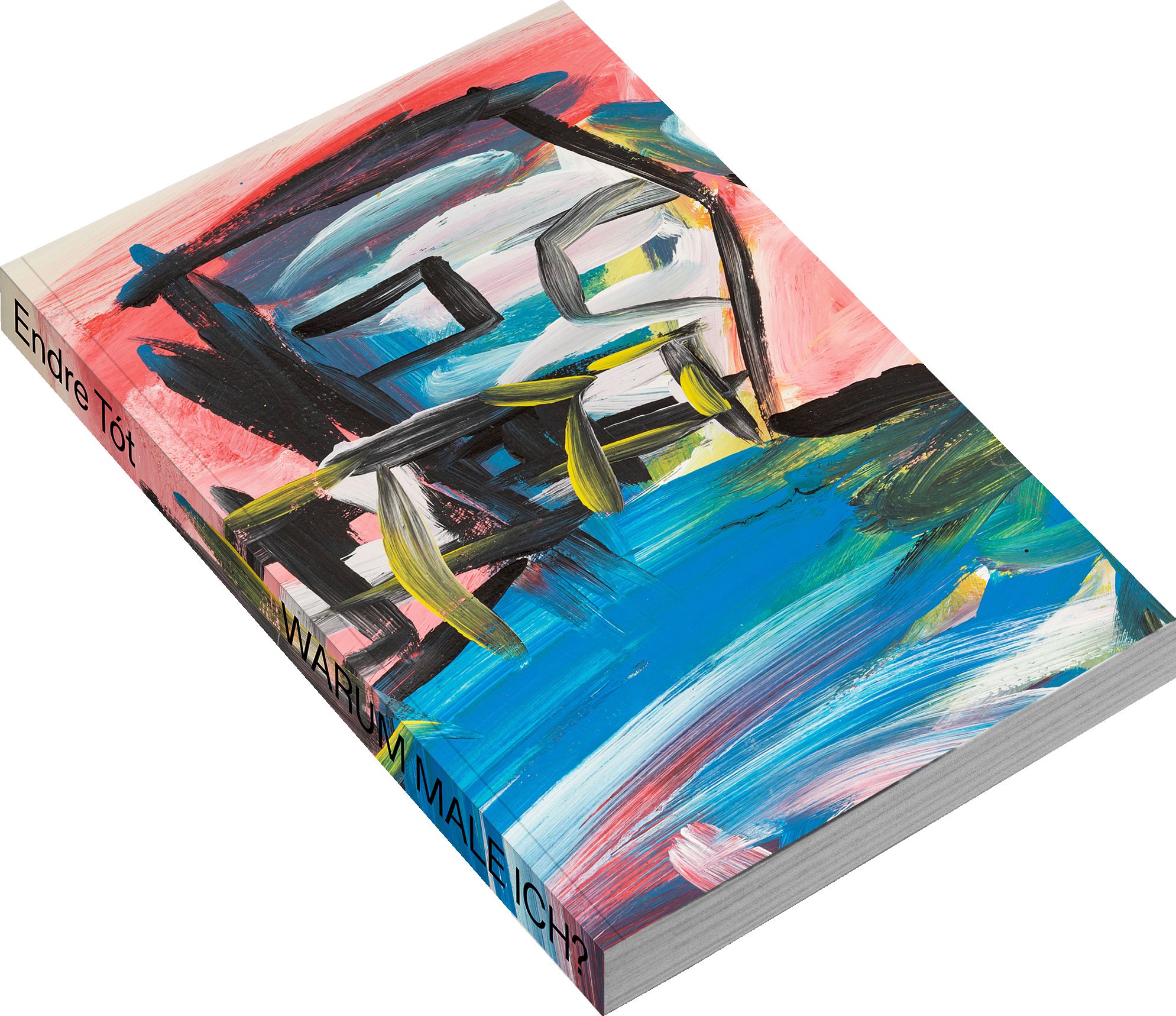

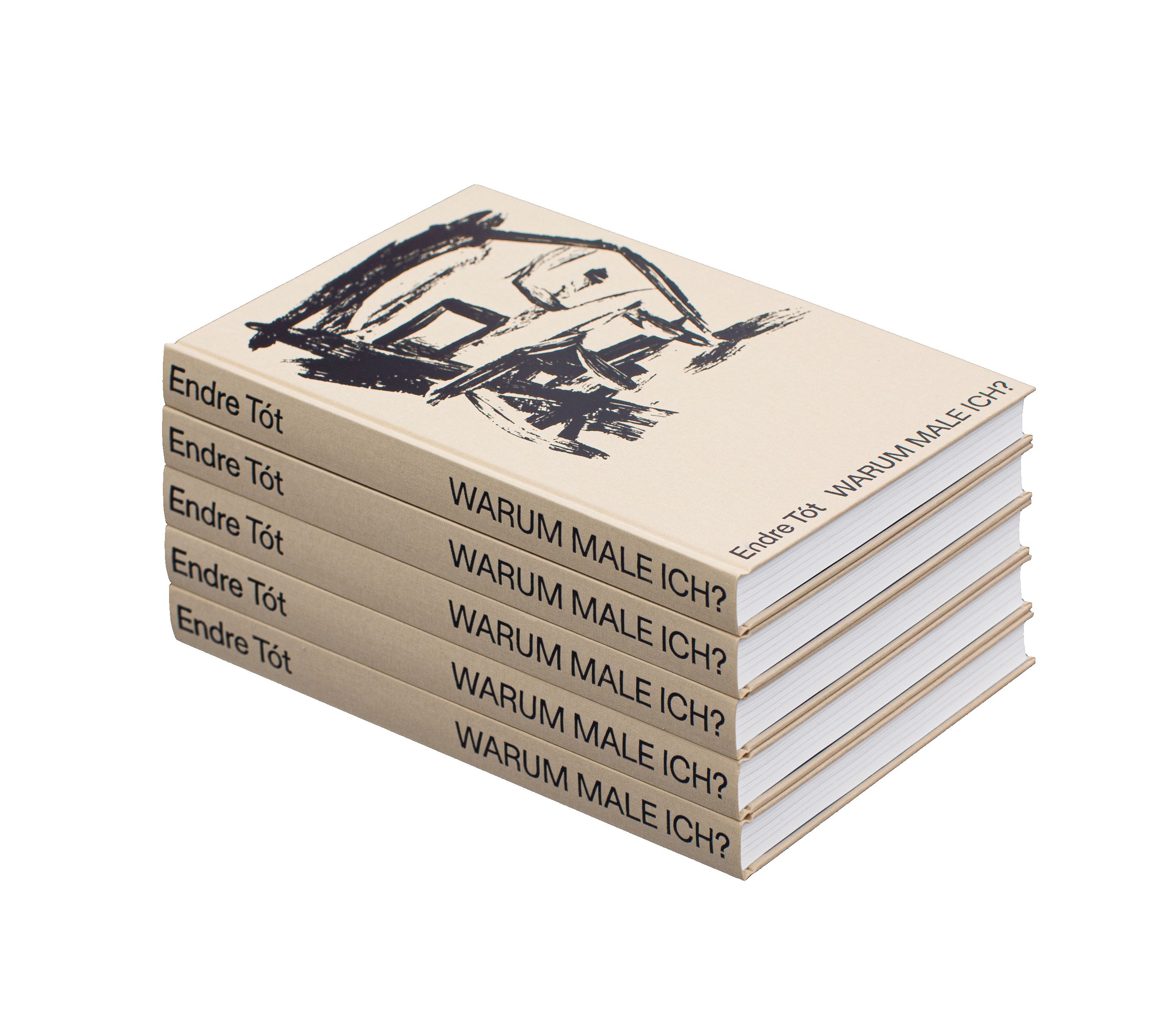

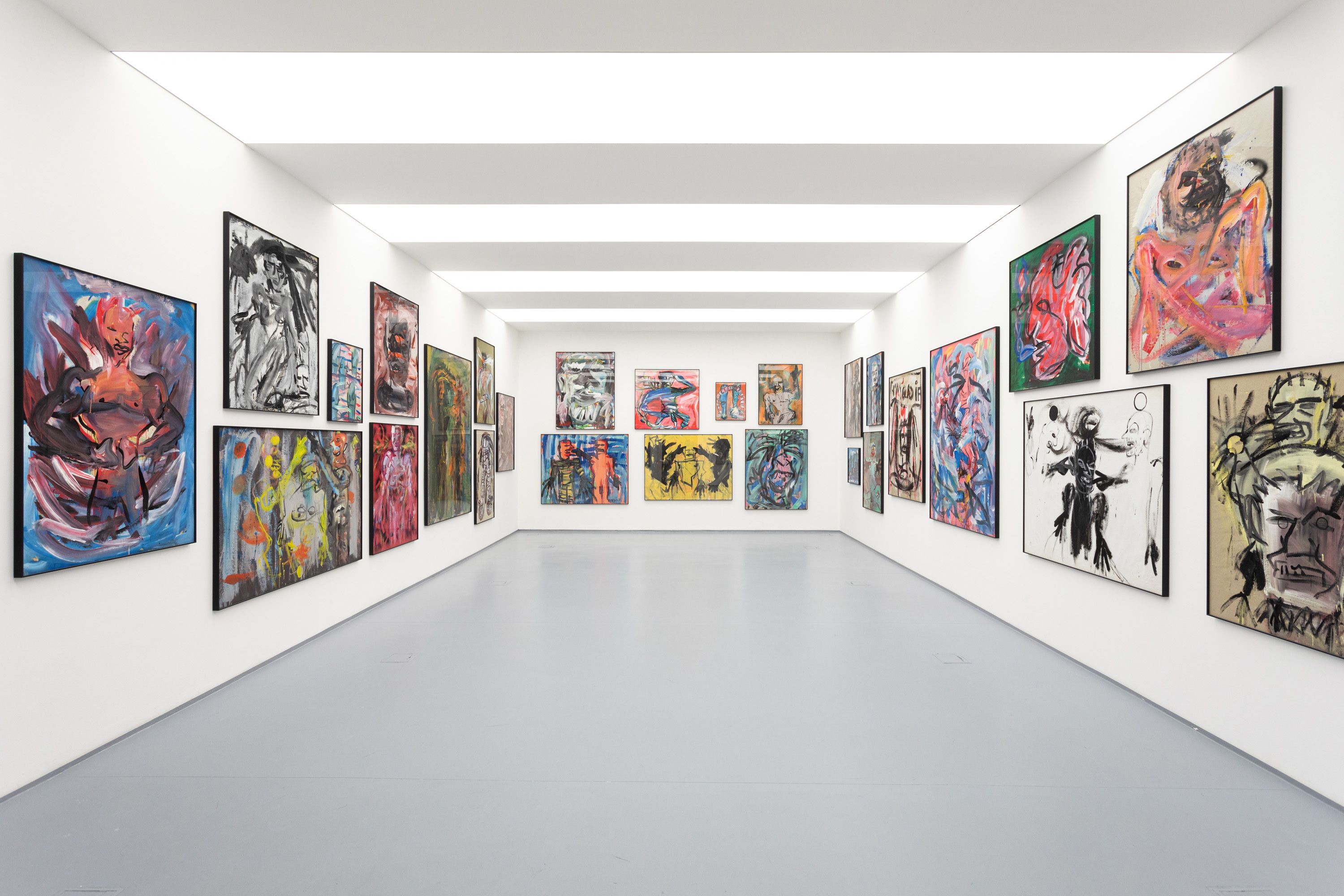

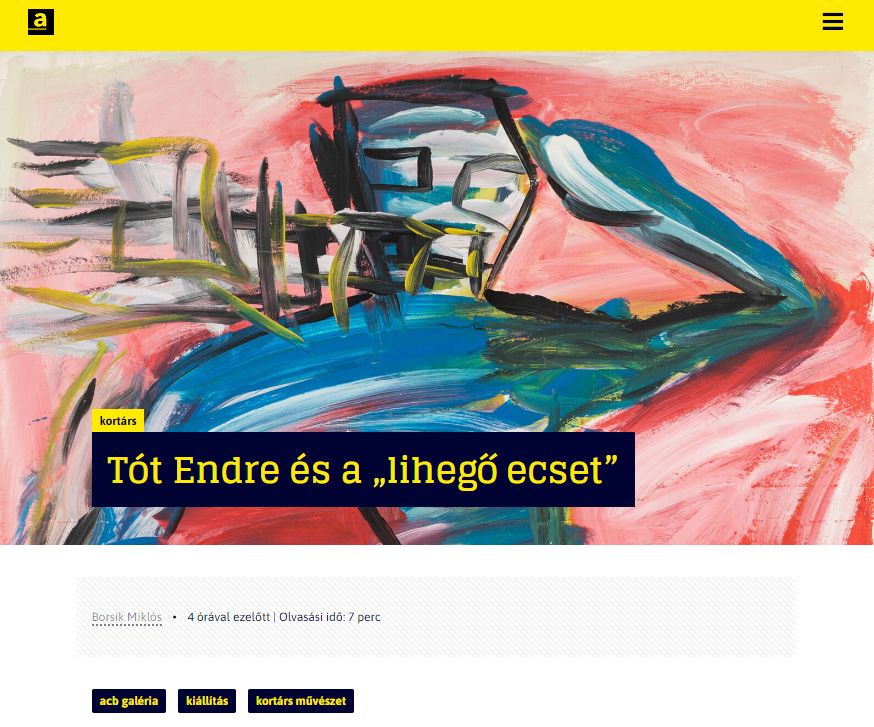

acb is proud to present its 8th, newest Viewing Room. In this VR, we introduce Endre Tót’s newly discovered painting series and exhibition, titled Warum male ich? (acb Gallery, Jul 01 – 29, 2022) through excerpts from the book published by acb ResearchLab featuring essays by art historians Dávid Fehér and Loránd Hegyi, as well as through the animation series created by Máté Fillér that tells the story of the conception and creation of the Warum male ich? painting series in Endre Tót's narration. For English subtitles, please make sure the CC button is turned on.

An introduction to the exhibition at acb Gallery, 1-29 July

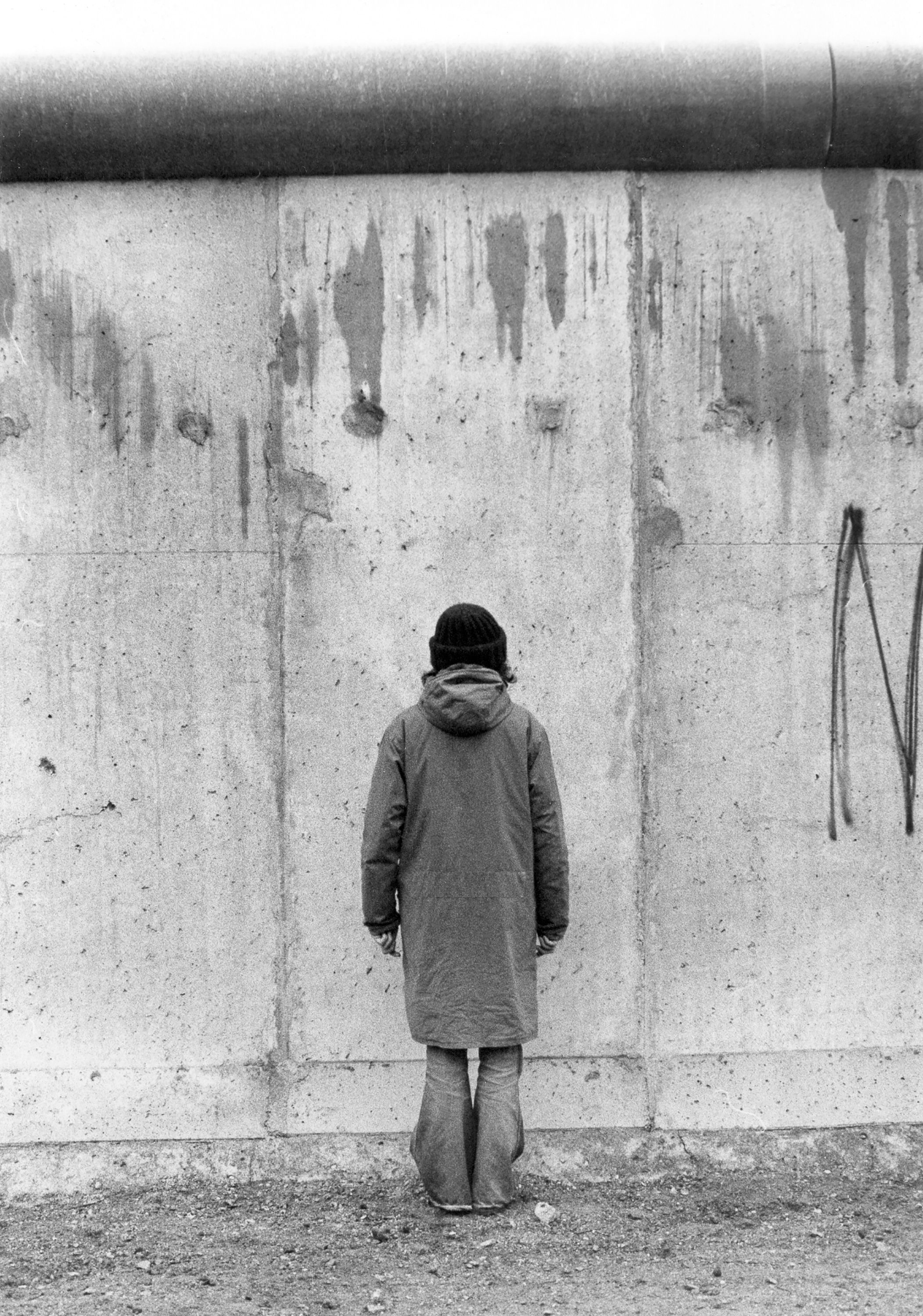

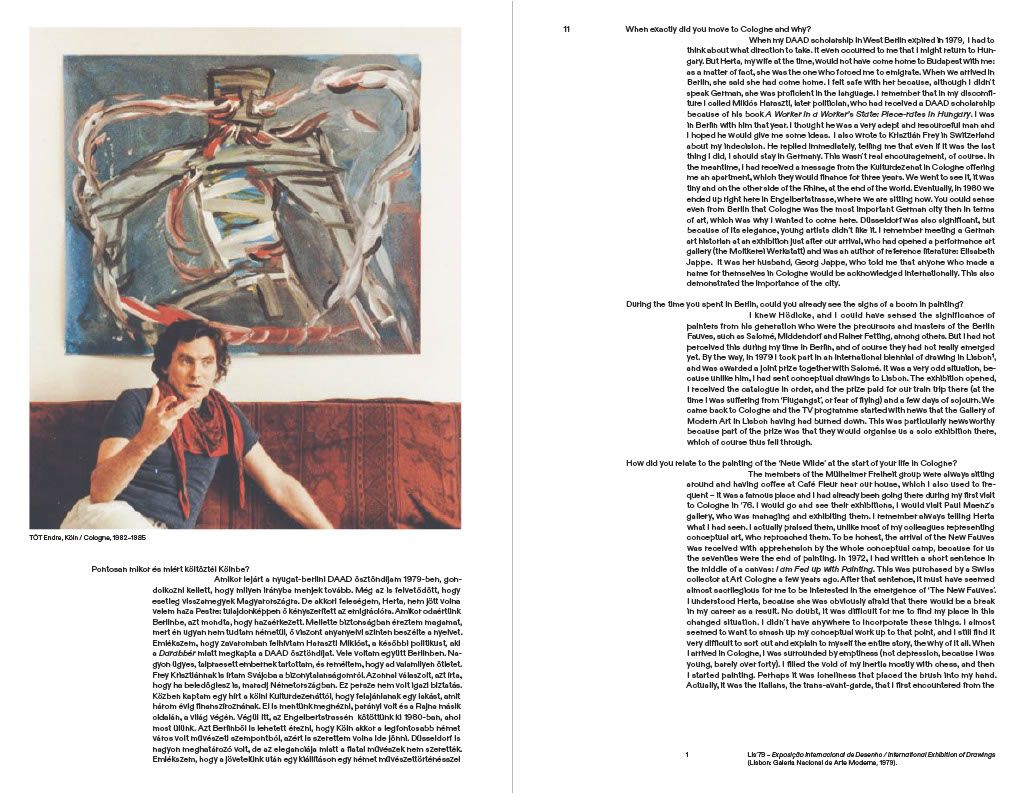

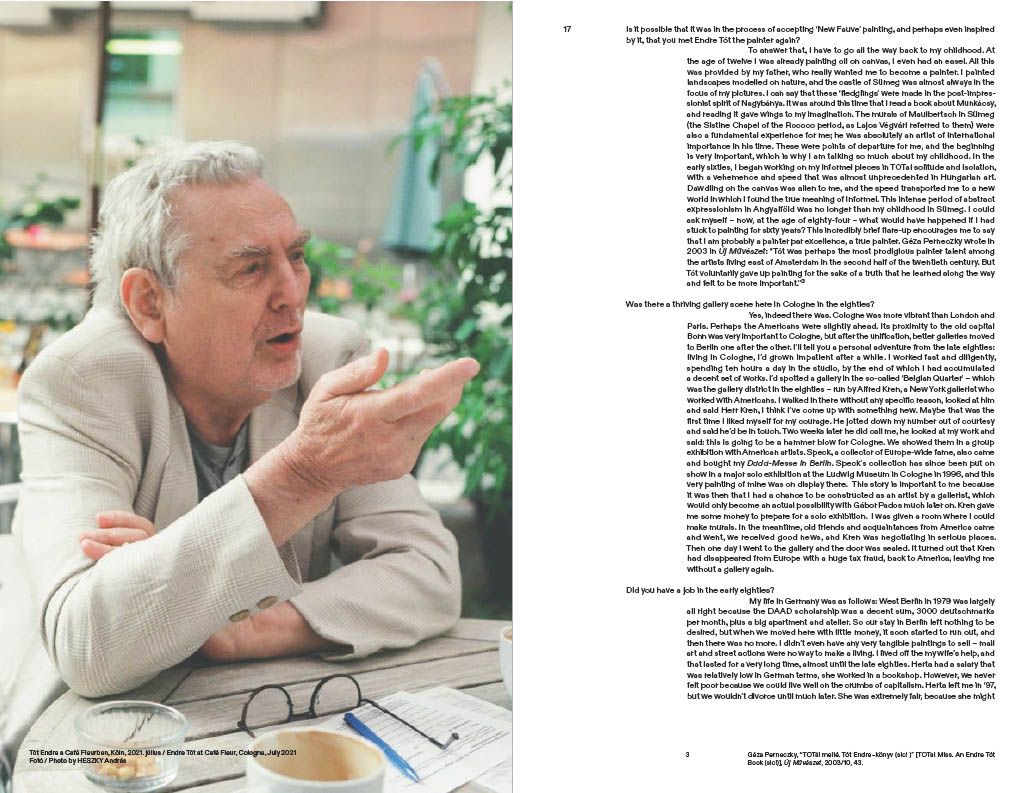

Endre Tót (b. 1937, Sümeg, Hungary), started out as a painter and became an recognized figure in both Hungarian and international conceptual art in the 1970s; once his DAAD scholarship in West Berlin expired, he moved to Cologne in 1980. Choosing emigration, Tót settled in the city on the Rhine at a time when European and North American exhibition venues were buzzing with exhibitions dedicated to the rediscovery of painting. These included Aperto, an open exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1980, A New Spirit in Painting in London in 1981, documenta in Kassel and Zeitgeist in Berlin in 1982, all of which signalled a “hunger for pictures” after a decade of dematerialized conceptual art. During this period, Cologne became one of the most important centres of neo-expressionist painting, hallmarked by a group of young artists called Mülheimer Freiheit, who were highly influential internationally.

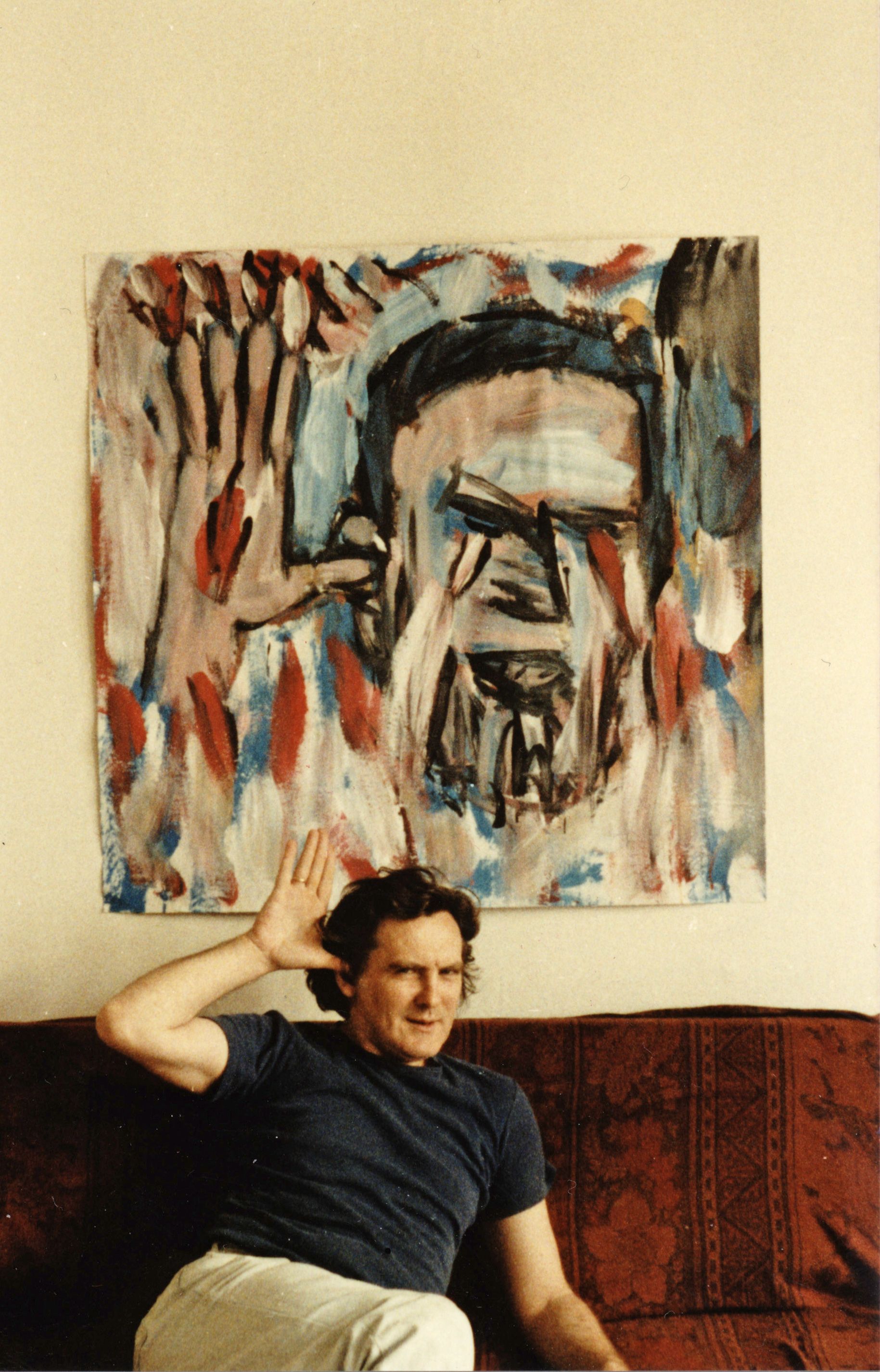

Until now, Endre Tót has said of his first years in the Federal Republic of Germany that, although he had a first-hand experience of the boom of new painting in the early 1980s, he remained outside it. From his time in West Berlin, he knew Karl Horst Hödicke, one of the artists of the first wave of German neo-expressionism who was close to him in generational terms, and living in Cologne, he witnessed the work of the “New Fauves”, the younger artists who were following in their footsteps. His outsider’s attitude was more of a distanced openness because of his past career as a painter in the 1960s, which had preceded his conceptual period. However, Tót remained silent for decades about the fact that he himself was painting again during this period.

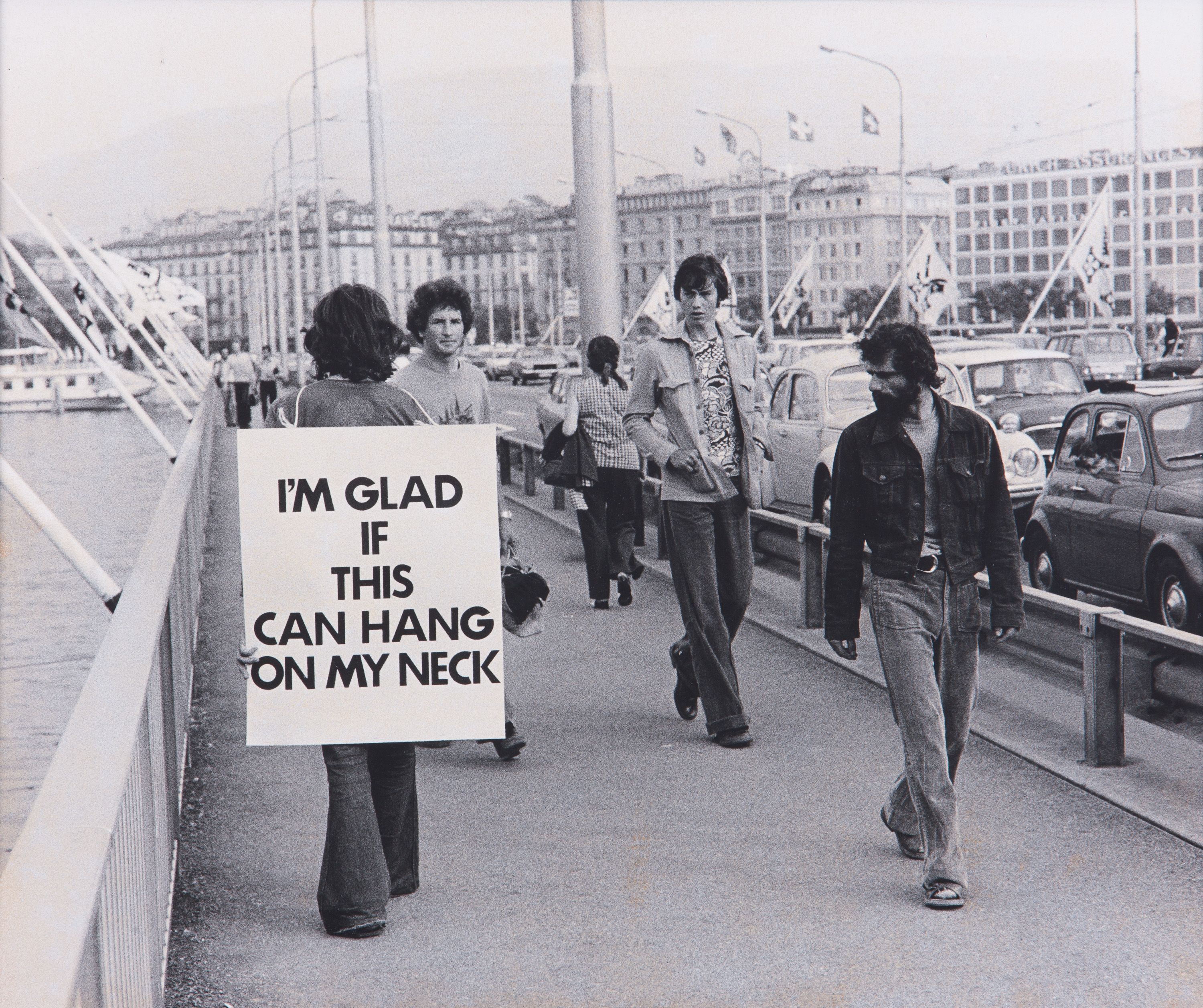

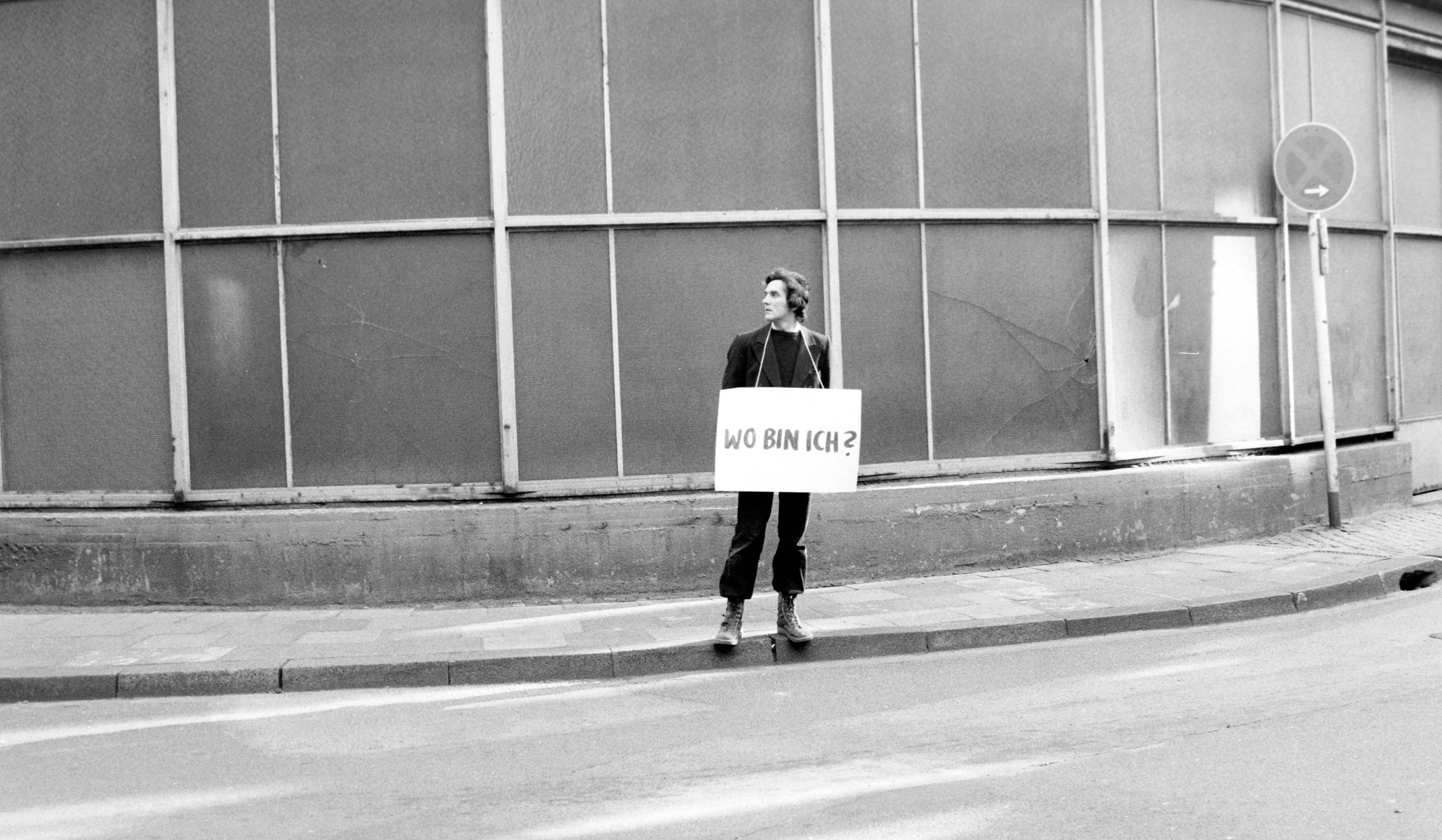

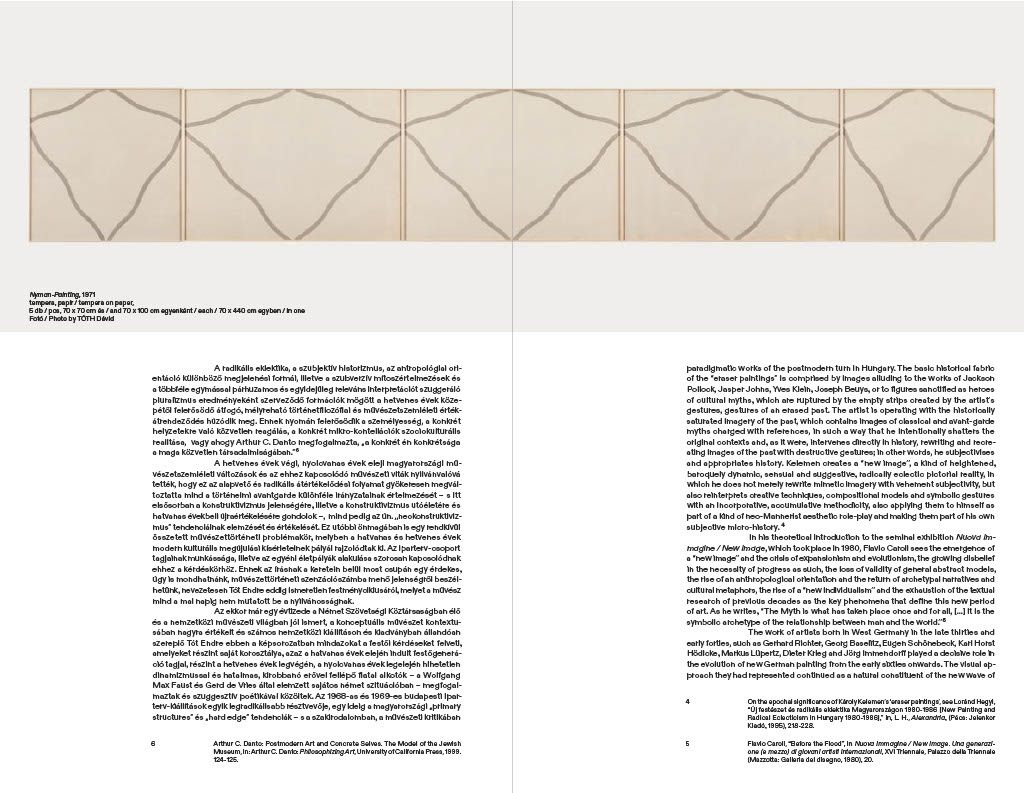

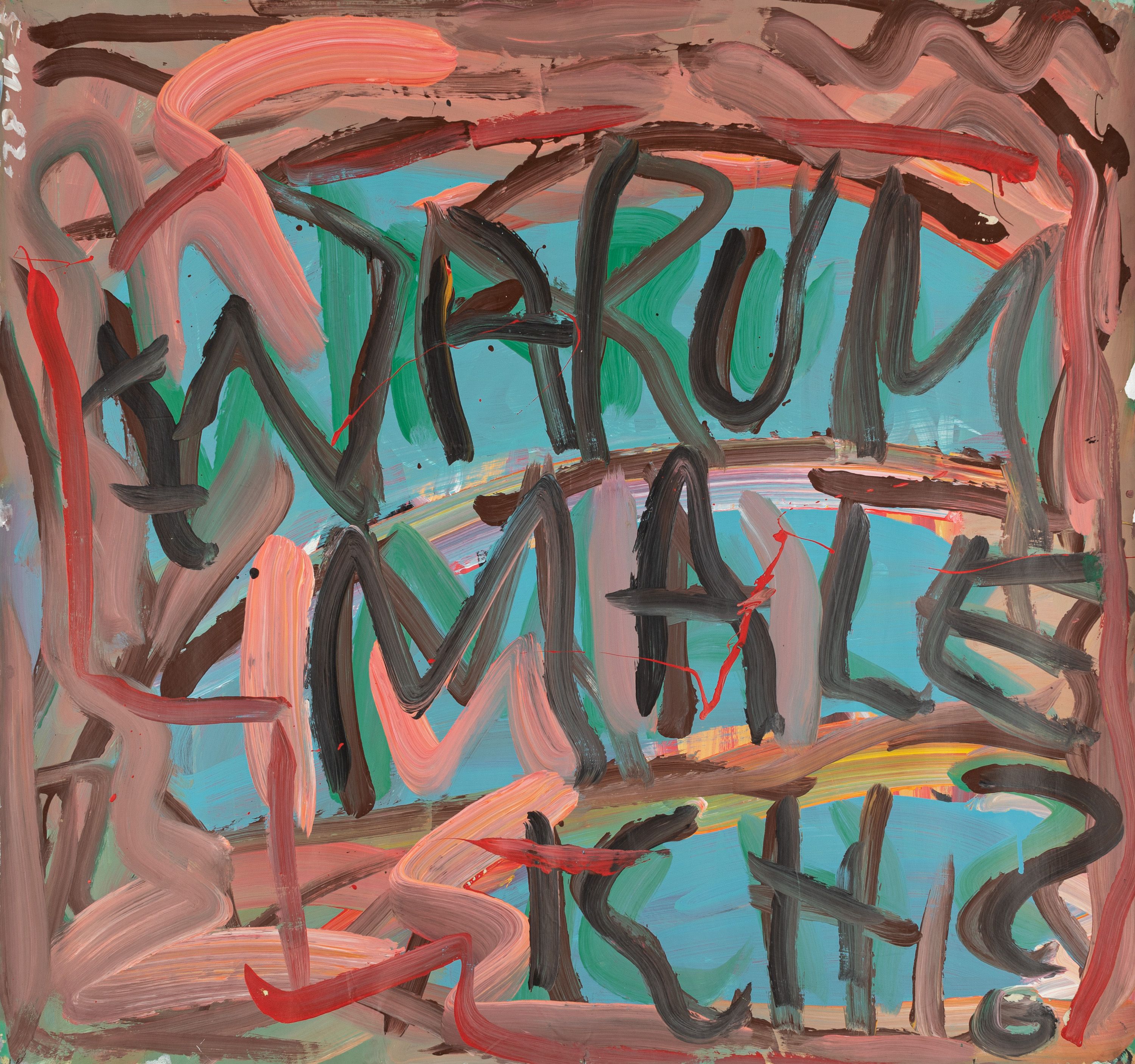

acb Gallery presented a selection from Tót’s newly discovered series, this extraordinary art historical speciality created with dynamic gestures and influenced by the Fauvist painting of the 1980s. The exhibition Warum male ich? focuses on the painter Endre Tót, an artist whose career, closely intertwined with conceptual art, has been dominated by theoretical and practical questions of painting and by his struggle with them, as evidenced by his artist books My Unpainted Canvases and Night Visit to the National Gallery in the early 1970s, then by his Absent Pictures, Blackout Paintings and Layout Paintings, also rediscovered by acb Gallery in 2019. Tót’s gesture-based early works, with which he participated in the legendary IPARTERV exhibition in 1968, were conceived in the spirit of intense painterliness, Abstract Expressionism, Informel, calligraphy, and then, in the late sixties and at the turn of the decade, his path led him to the emptying of the canvas, to a break with the medium, often through Pop Art Hard-Edge as well as minimalist works, and at the same time to conceptual art. His concepts of “Zero” and “Nothing” have appeared in mail art, street demonstrations, photo performances, typewritten works, stamp works, offset works and artist books, not infrequently through references to painting.

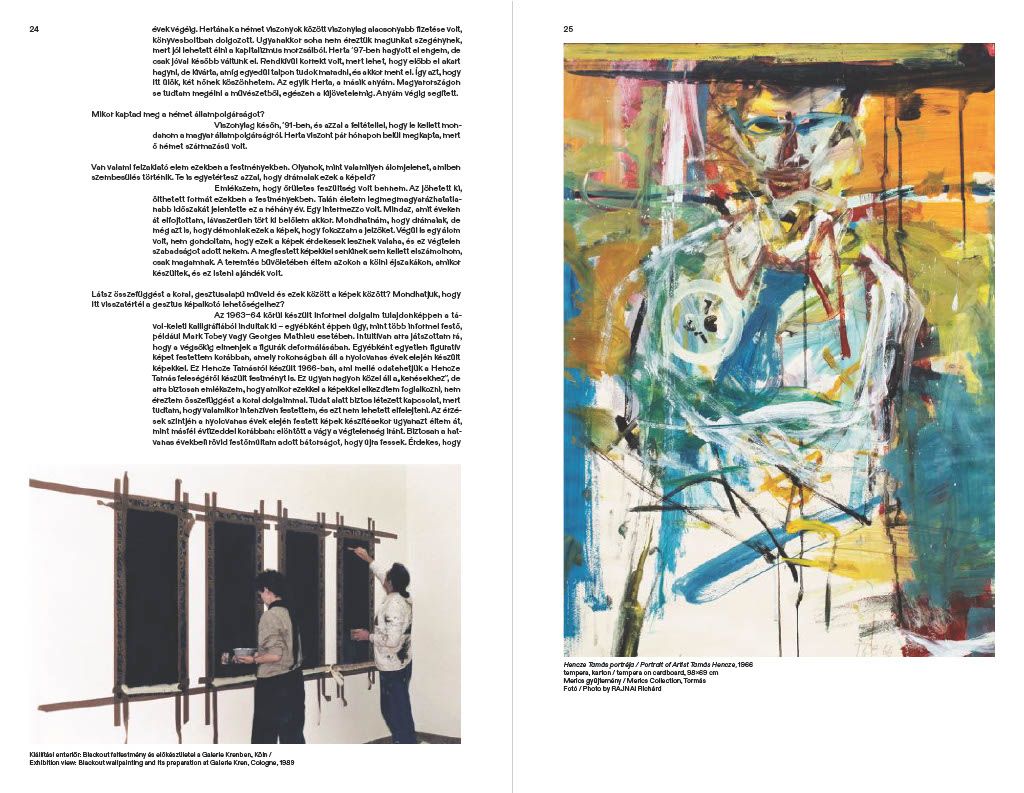

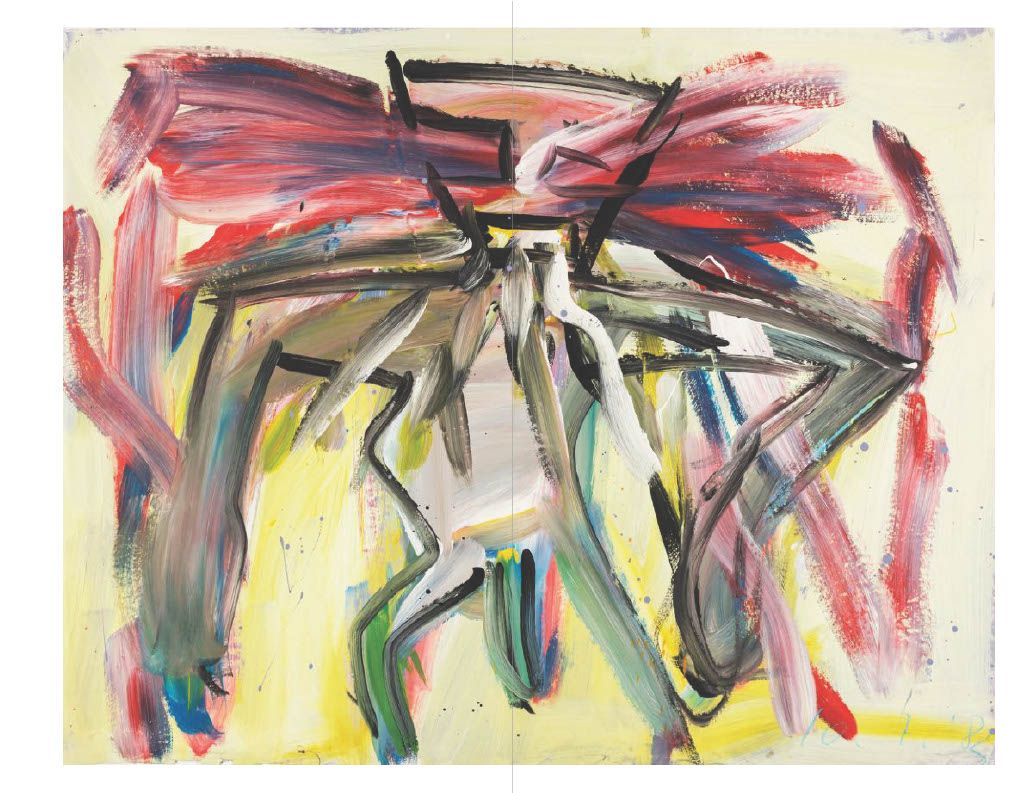

Conceived in secret, the newly discovered works are most closely related to Endre Tót’s early, expressive works, especially the figurative paintings that we know today from the portrait paintings of Tamás Hencze and his wife made in 1966 with wild brushstrokes. And the precise dating of some of the pieces links these paintings – which can also be understood as a chronicle of confinement, passing days and the mystery that comes from the personal – to the light calligraphic drawings of the mid-1960s, the Diary Drawings from Angyalföld. The works of the Warum male ich? cycle are dominated by gestures and the relationships between the depicted figures: the overall effect of the pictures is at once dramatic and ironic, occasionally caricature-like, but the pictures certainly radiate a liberating, intense experience of ‘hot’, gesture-based painting, the pure painting that has essentially defined Endre Tót’s creative career all along. The exhibition takes its title from a piece in the series – Why Do I Paint? – which self-revealingly refers to Tót’s dilemmas about painting as he took up the brush again in the early 1980s. By the end of the decade, Tót had become an active figure in the Cologne art scene. His Layout-, Blackout Paintings and Absent Pictures, which can be read as a synthesis of painting and conceptual endeavours, became the dominant body of his work in the following years. His 1995 retrospective at Műcsarnok / Kunsthalle Budapest and the 1999 exhibition Who’s Afraid of Nothing at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne focused the public’s attention on Endre Tót’s canonical works, which the Warum male ich? paintings at acb Gallery’s exhibition not only augmented with a new cycle but they also allowed us to see Endre Tót’s career, creative spirit and artistic character through a new lens.

Loránd Hegyi: Coherence and Sensuality. Notes on Endre Tót’s Cycle of Paintings Warum male ich? (1982-1985)

Endre Tót’s hitherto unknown expressive painting cycle, whose circumstances of conception the artist has been reticent about so far, is not merely a curiosity, nor is it just an interesting biographical episode. The 'Primary Structures' programme of Endre Tót’s earlier years had been part of the mainstream of international ‘post-painterly abstraction’ and stood out with its extraordinary consistency in the artistic developments of the sixties. The objectivity of geometric forms, stripped of all anecdotal elements and personal narratives, the anti-hierarchical, indifferent, material character of elementary, simple yet unusual compositions, the radical transparency of the visual phenomenon unrelated to any kind of extra-pictorial moment, the radicalism of the autonomy of the self-referential visual sign, were completely new phenomena in the Hungarian art of the sixties. Not even Hencze’s structural works of the time, which are most comparable to Endre Tót’s works between 1966 and 1970, convey such a degree of material objectivity and such an elimination of possible narratives from the visual structure. Interestingly, both artists had taken the American tradition of ‘action painting’ as their point of departure, in a manner radically different from István Nádler, Imre Bak, or Sándor Molnár, who felt the introverted, meditative, romantic and somewhat pantheistic emotionalism of European ‘Lyrical Abstraction’ and ‘Tachism’, represented above all by Manessier, Estève, Riopelle and Soulages, closer to their own perception of art. However, while Tamás Hencze’s early gestural paintings remained free of any mimetic elements, always working with a par excellence non-representational, abstract visual language, Endre Tót’s mostly small-scale paintings of the early sixties mix purely impulsive, non-representational gestures with certain mimetic elements, primarily portraiture.[1] The influence of late fifties and early sixties American painting, especially the ‘pre-Pop-Art’ of Larry Rivers, is even more evident in these works. One of the main intentions of Larry Rivers’ brilliant art, which reformed American painting, was to capture contemporary urban, banal, everyday reality through the sublimating creation of spectacles characteristic of the ‘Grand Masters’, the tradition of European classical painting. Larry Rivers’ motifs and subjects were identical with those of Pop Art, the material reality of American metropolitan industrial civilization, but instead of an objective representation of the alienated, depersonalized object, he transformed the banality of objects into a sublime, painterly image structure. His painterly gestures sometimes recall the brushwork of Frans Hals or Manet, sometimes the light effects of the Impressionists, their poetic rendering of a material world washed out by silvery tones.

[1] While visiting Tamás Hencze’s apartment in the 1970s, the author saw early portraits by Endre Tót, which bore the stylistic traits of Portrait of Tamás Hencze (1966) and Portrait of Mrs. Tamás Hencze, and were made in roughly the same period. (the ed.)

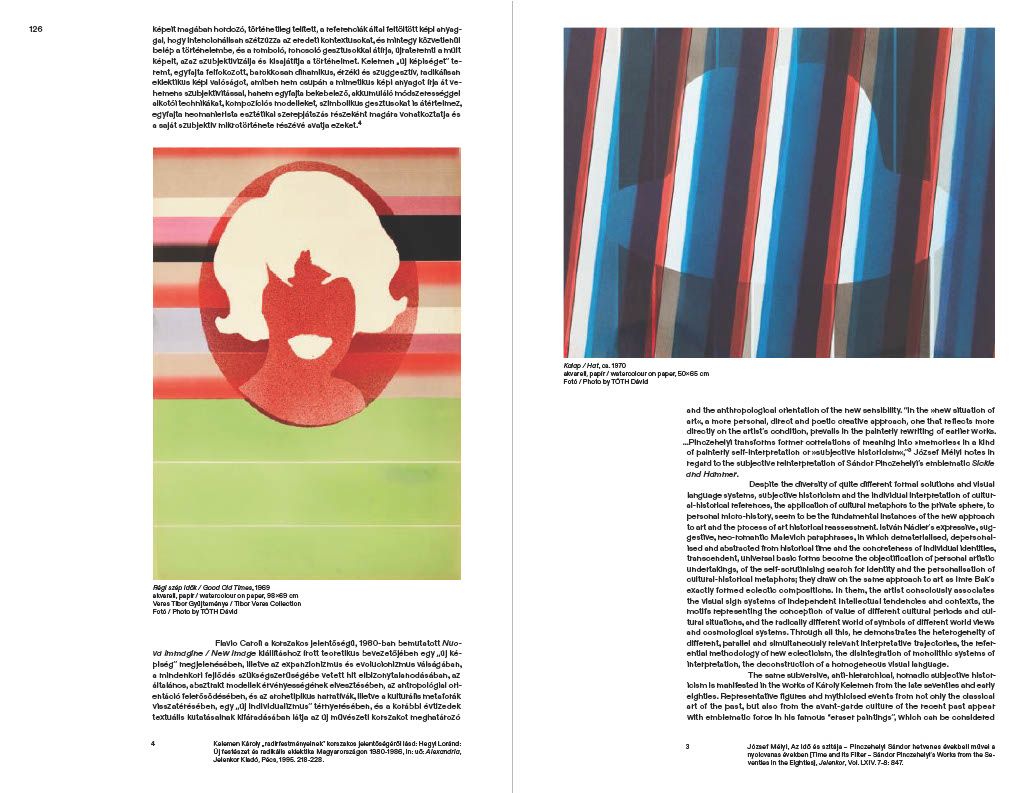

It is this complex moodiness, this rewriting and ambiguation of material motifs that characterises the young Endre Tót’s painting praxis, expressed in a highly refined and subtle use of colours. He is also characterised by a peculiar Larry Riversian melancholy, which transposes the visible, immediate, banal material reality into a poetically transubstantiated medium. What is indeed surprising when one looks at the expressive Cologne cycle of paintings is the reappearance of this subtle, slightly decadent, elegant and melancholy use of colour and the mood it conveys in works that are essentially radically existential in their content. While the expressive paintings of the Cologne cycle are characterised by a sternness that conveys basic existential situations and conflicts, and a radical austerity that is simplistic like a model and strips away all anecdotal narrative and literary detail, and while the repetitive and mechanical lining up and almost automatic moving around of figures stripped-down to a symbolic level suggest a cold impersonality, in fact, the colours of a significant part of the paintings bring back the subtle tones characteristic of the early sixties, the delicately mixed silver-grey - pink - brownish-red and grey - pale blue - green shades. This subtle colourism, the lyricism of the colours and their potentially mood-charged character distinguishes the imagery of Endre Tót’s Cologne paintings quite sharply from the more poster-like aggression of the younger generation of German artists of ‘Mülheimer Freiheit’ and ‘heftige Malerei’, who worked with pure and powerful tones, and instead shows some affinities with the paintings of a few artists who were mostly the same age as Endre Tót, especially Karl Horst Hödicke and Dieter Krieg.

(…)

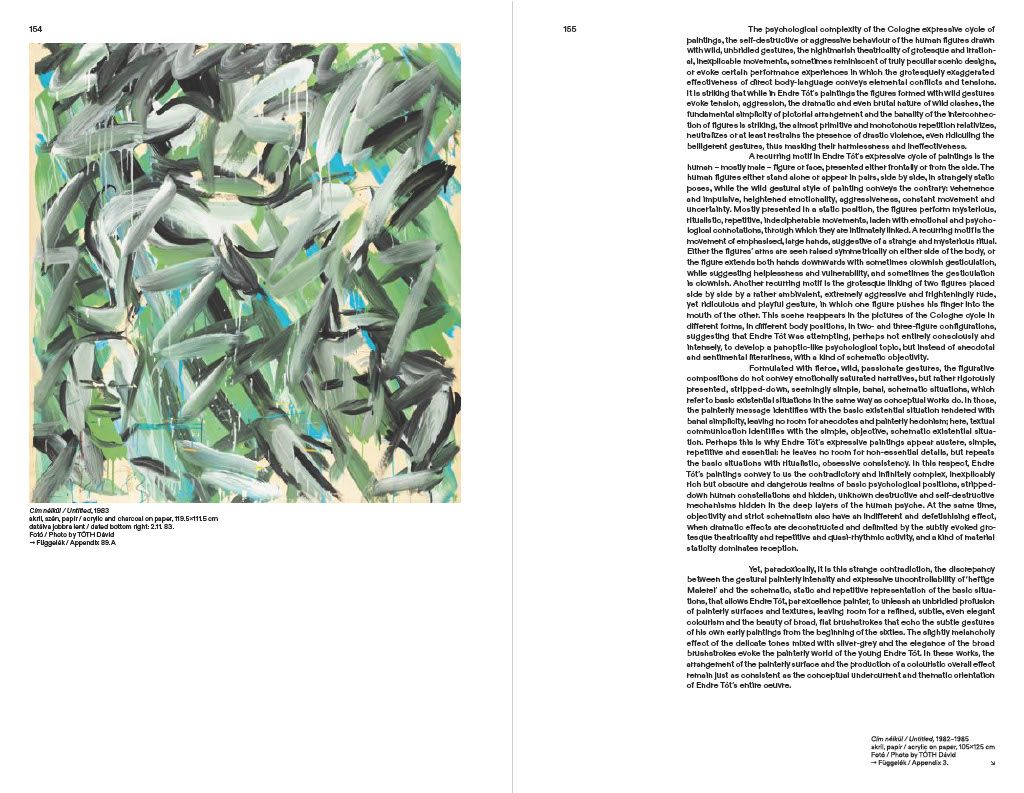

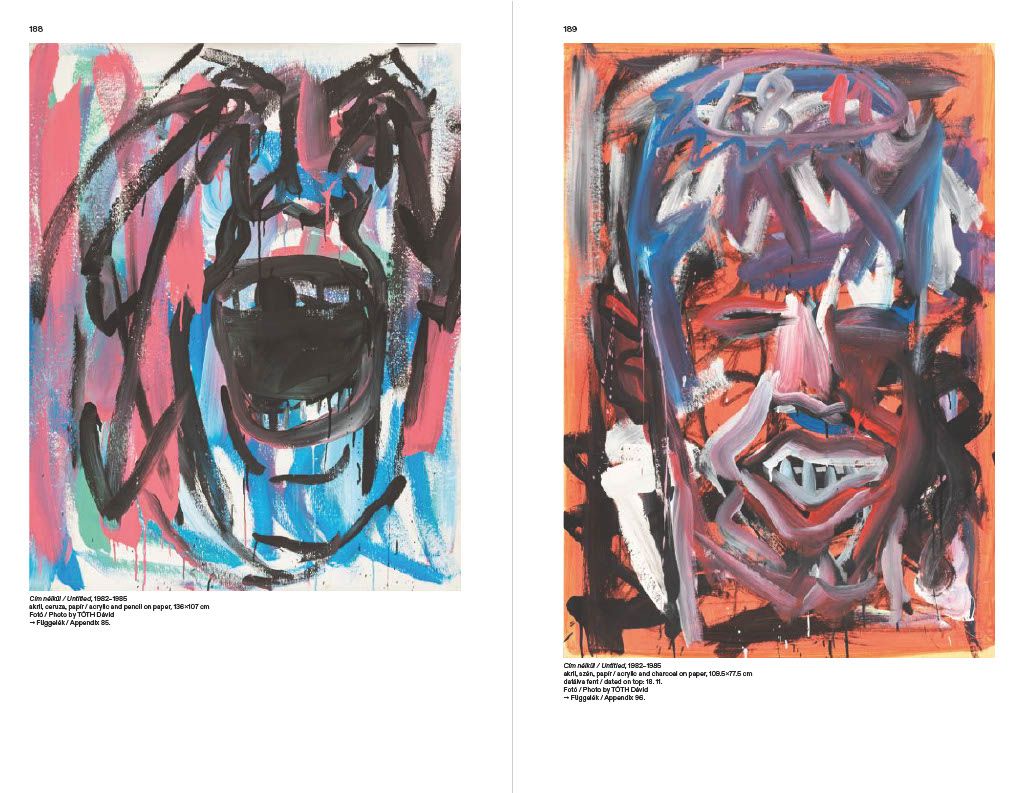

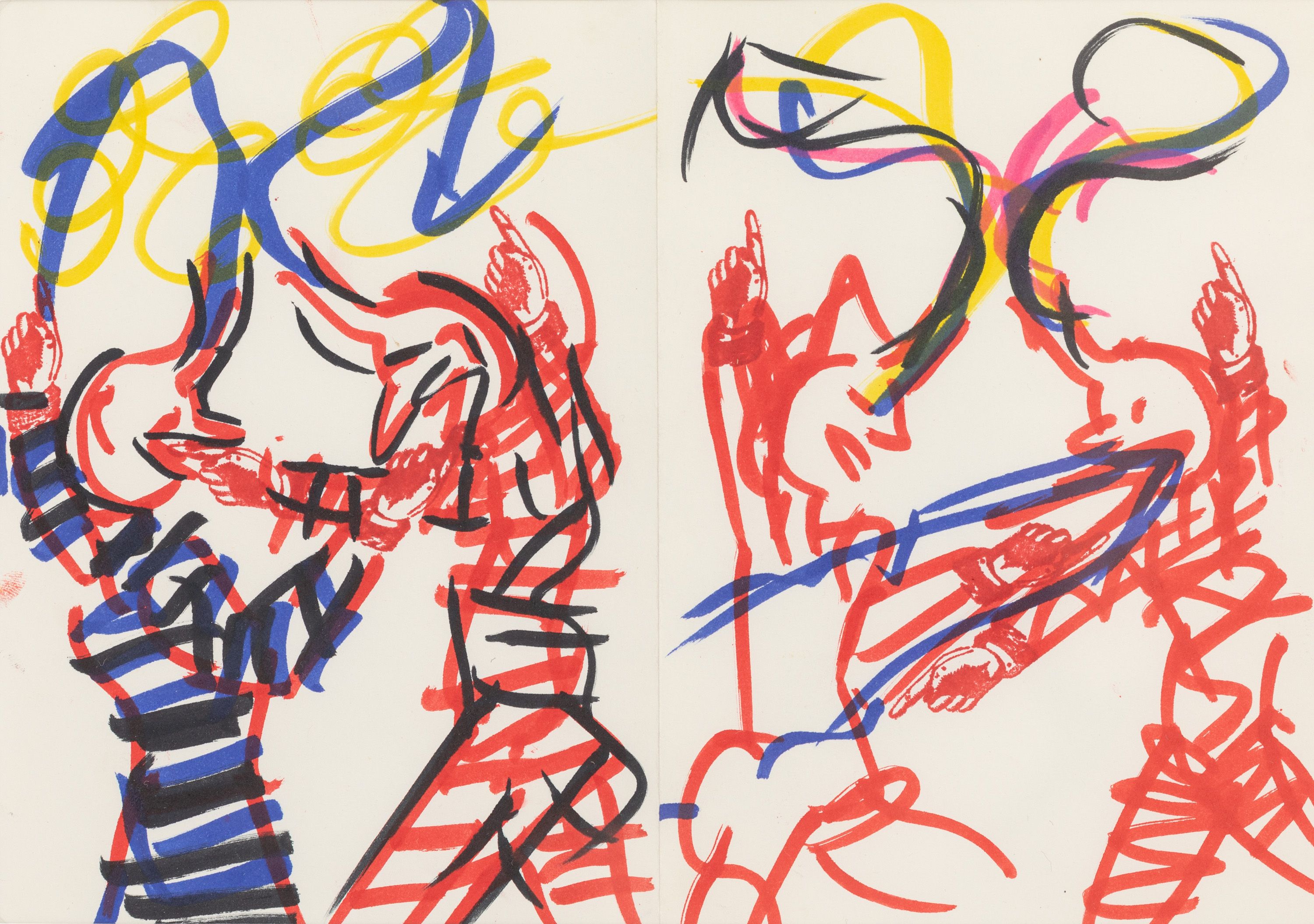

The psychological complexity of the Cologne expressive cycle of paintings, the self-destructive or aggressive behaviour of the human figures drawn with wild, unbridled gestures, the nightmarish theatricality of grotesque and irrational, inexplicable movements, sometimes reminiscent of truly peculiar scenic designs, or evoke certain performance experiences in which the grotesquely exaggerated effectiveness of direct body-language conveys elemental conflicts and tensions. It is striking that while in Endre Tót’s paintings the figures formed with wild gestures evoke tension, aggression, the dramatic and even brutal nature of wild clashes, the fundamental simplicity of pictorial arrangement and the banality of the interconnection of figures is striking, the almost primitive and monotonous repetition relativizes, neutralizes or at least restrains the presence of drastic violence, even ridiculing the belligerent gestures, thus masking their harmlessness and ineffectiveness.

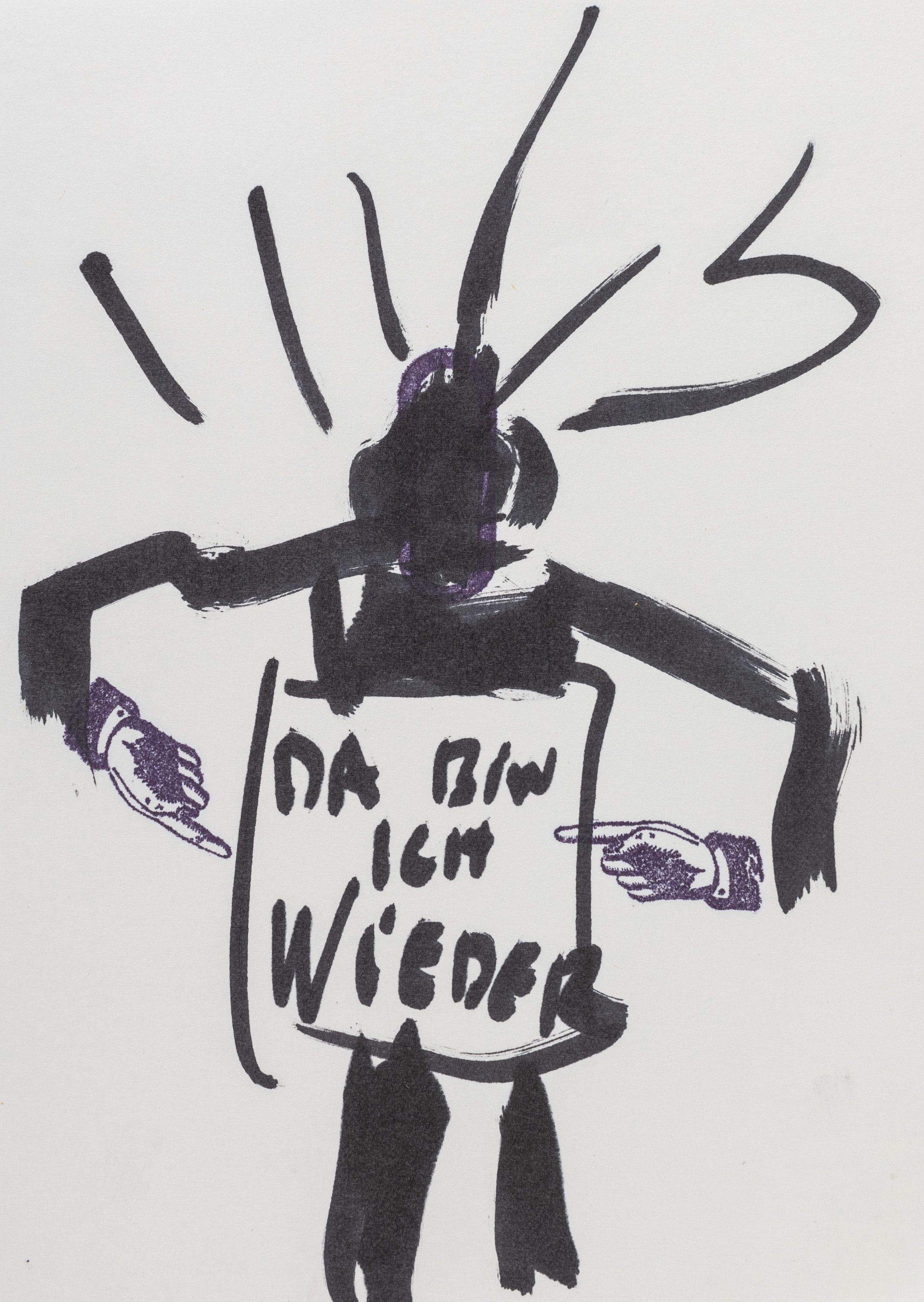

A recurring motif in Endre Tót’s expressive cycle of paintings is the human – mostly male – figure or face, presented either frontally or from the side. The human figures either stand alone or appear in pairs, side by side, in strangely static poses, while the wild gestural style of painting conveys the contrary: vehemence and impulsive, heightened emotionality, aggressiveness, constant movement and uncertainty. Mostly presented in a static position, the figures perform mysterious, ritualistic, repetitive, indecipherable movements, laden with emotional and psychological connotations, through which they are intimately linked. A recurring motif is the movement of emphasised, large hands, suggestive of a strange and mysterious ritual. Either the figures’ arms are seen raised symmetrically on either side of the body, or the figure extends both hands downwards with grotesque awkwardness, while suggesting helplessness and vulnerability, and sometimes the gesticulation is clownish. Another recurring motif is the grotesque linking of two figures placed side by side by a rather ambivalent, extremely aggressive and frighteningly rude, yet ridiculous and playful gesture, in which one figure pushes his finger into the mouth of the other. This scene reappears in the pictures of the Cologne cycle in different forms, in different body positions, in two- and three-figure configurations, suggesting that Endre Tót was attempting, perhaps not entirely consciously and intensely, to develop a panoptic-like psychological topic, but instead of anecdotal and sentimental literariness, with a kind of schematic objectivity.

Loránd Hegyi

Dávid Fehér: Warum male ich? Painting and Suppression in the Art of Endre Tót

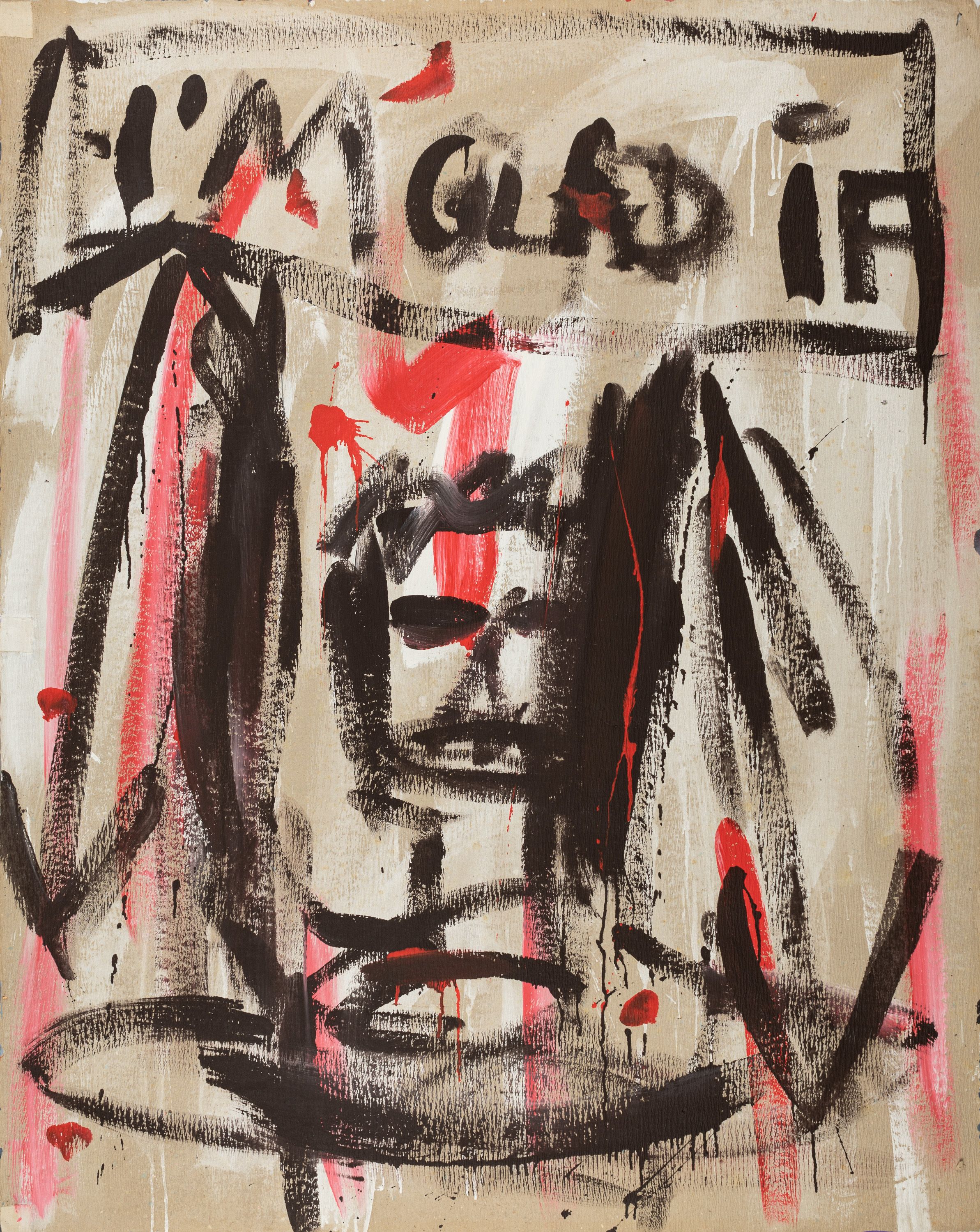

Endre Tót: Untitled

acrylic on paper 150 × 120.5

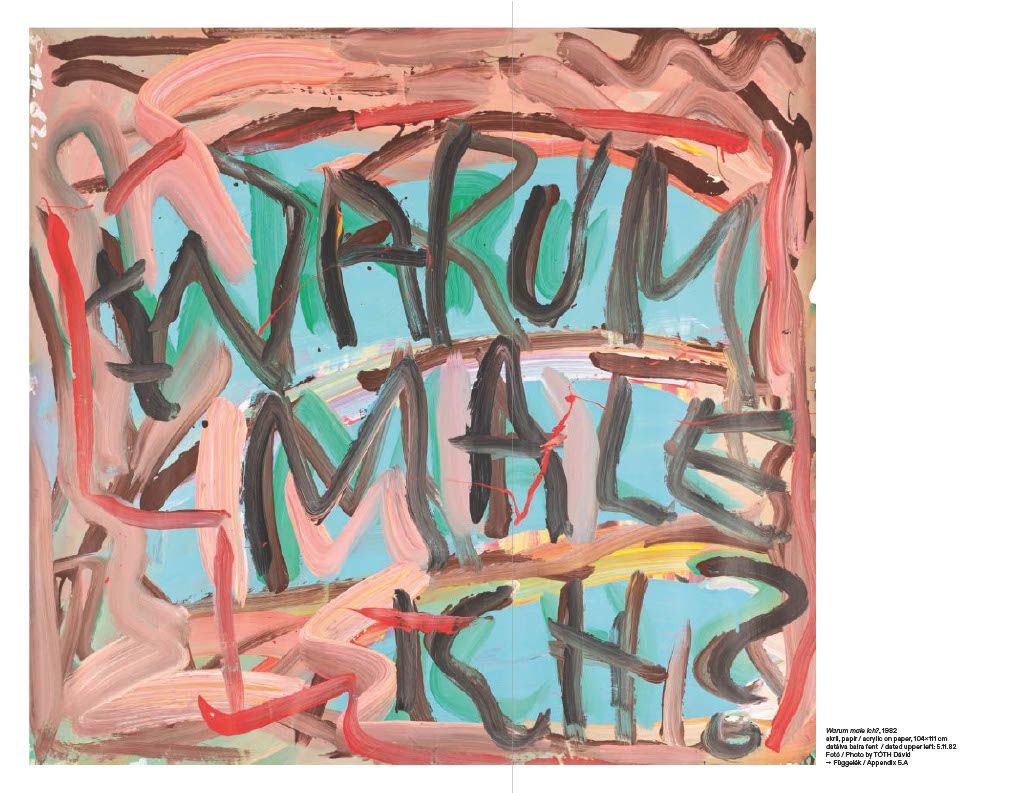

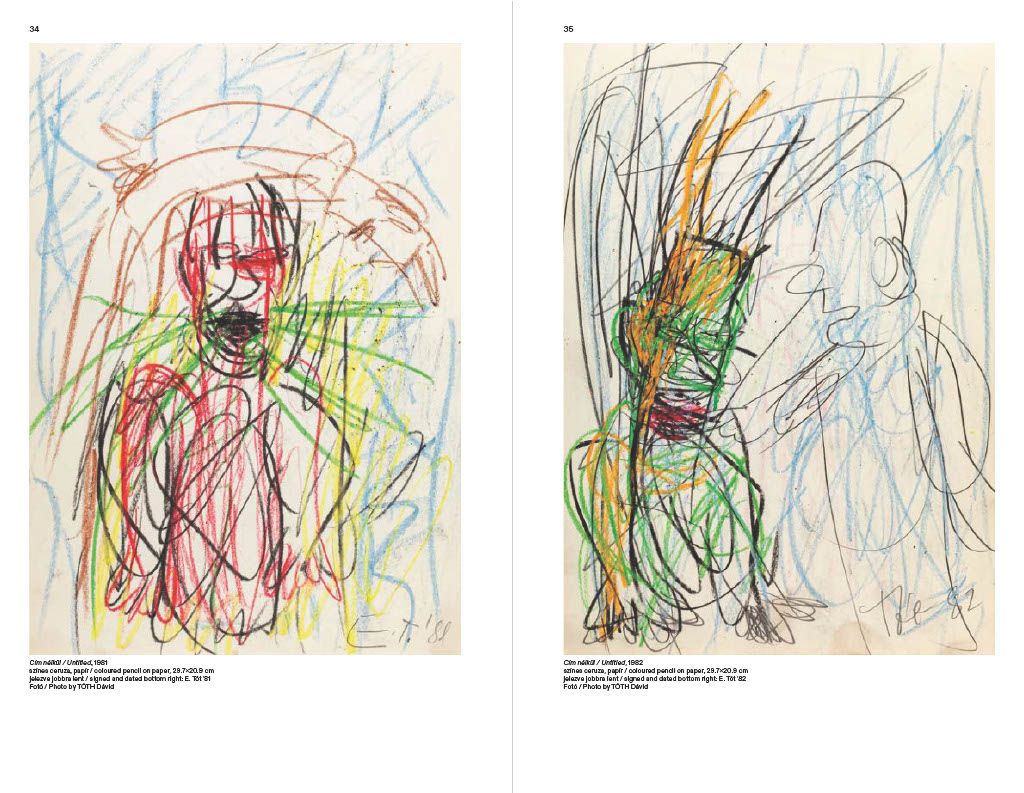

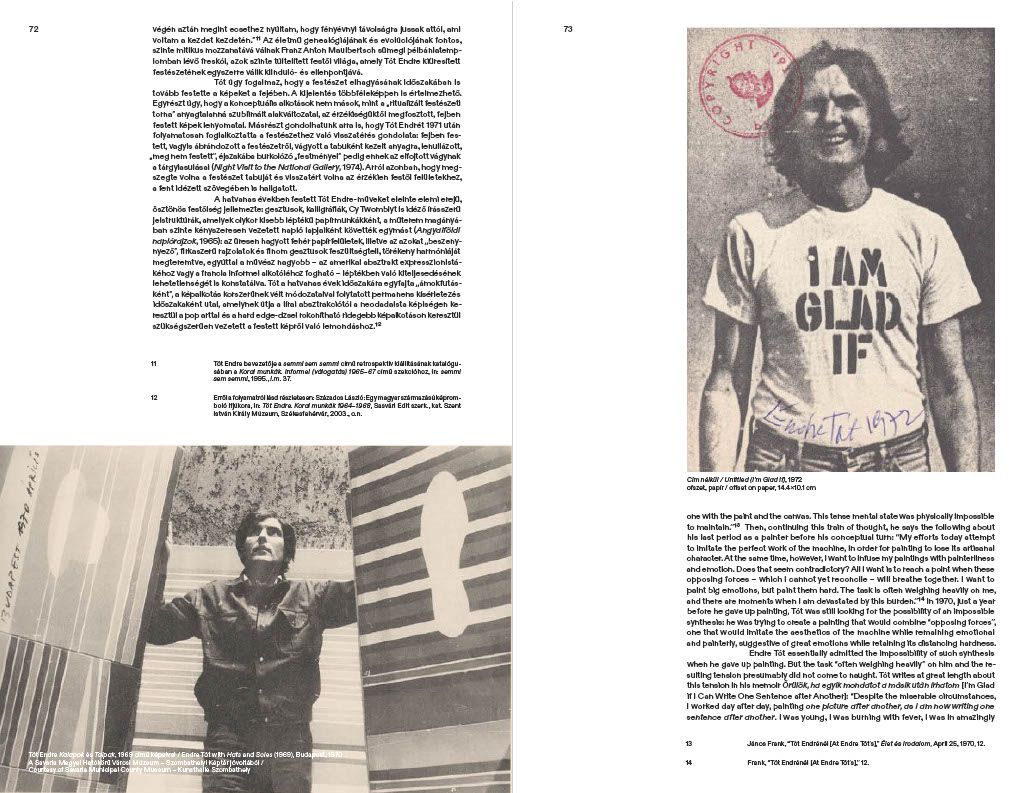

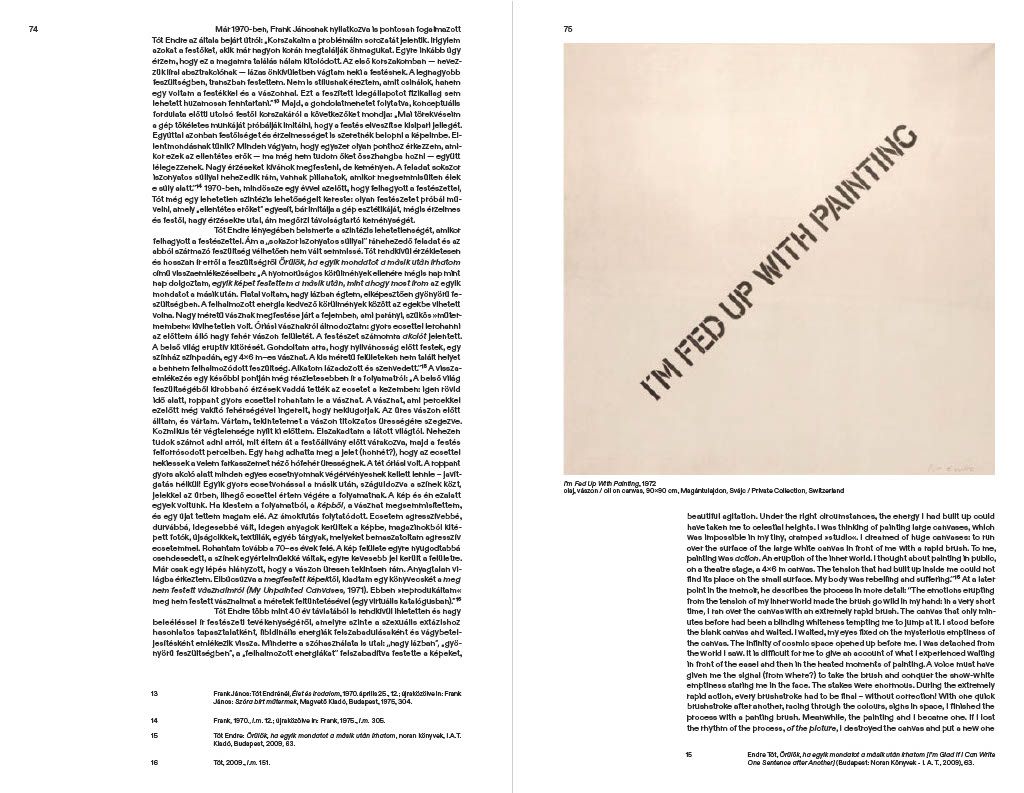

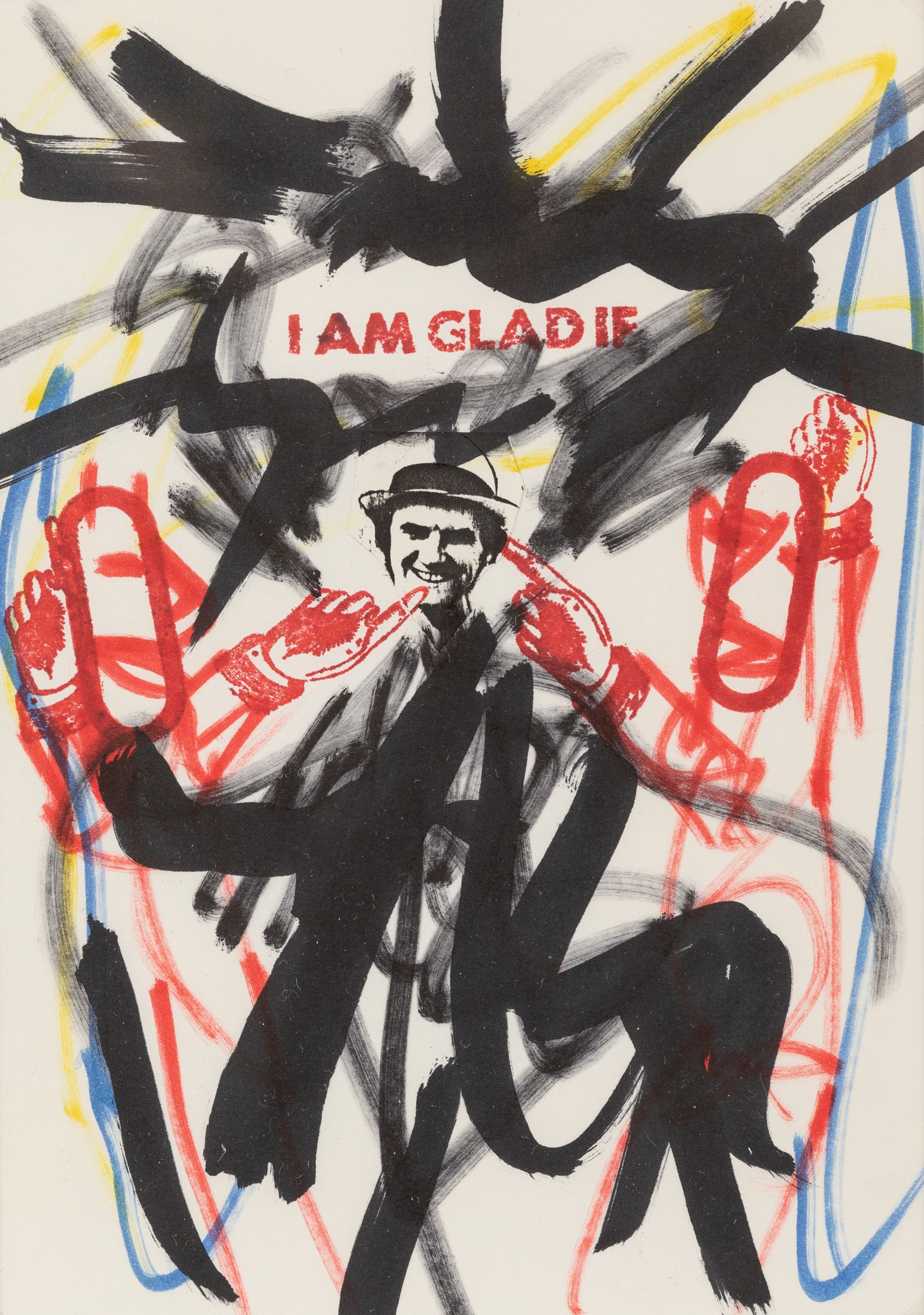

A number of Endre Tót’s “wild” paintings from the period between 1982 and 1985 feature the inscription Warum male ich? (Why Do I Paint?). The question seems to continue the sentence on the painting from about a decade earlier: “I’m fed up with painting, why do I paint?” The entire surface of the paintings is filled with intensely coloured, rampant painterly gestures, reminiscent of Endre Tót’s early works. The works from between 1982 and 1985 were presumably created in the same manner as the works from 1962 to 1965 – in a feverish rush, he “jumped at” the empty paper surface, and instead of nothing, he began to create again enchanted by everything. Rather than emptying the image field, he filled it up, leaving no empty surface – just an orgiastic play of layers of full-blooded paint on top of each other, burying very thing underneath. Painting had once again “sullied” the void that dominated Endre Tót’s art. The text, which literally overwrites the abstract surface of the image, seems to reflect on the creative process in retrospect: the inscription superimposed on the instinctive painterly gestures questions the very artistic activity itself. This time painting is not turning against, but querying itself. In some of his paintings from this period, Tót evokes iconic motifs from his conceptual works: the question “which is the right direction?” is accompanied this time by spray-painted gestural, squiggly arrows, reinterpreting the original question: which is the right direction between the negation of painting and the return to painting? In another case, the inscription “I'm glad if” appears above a stylised head, although in a different composition, another text warns that the muscular, stylised male figure is “not a self-portrait” (keine selbsportre [sic!]). The two inscriptions are revealing: on the one hand, Tót summons his own iconic motifs, while on the other hand, he denies the self-portrait character of the works. However, in the drawings he produced in parallel with the paintings, the heads of the stylised figures are often replaced with a photograph of his own face. The works can also be seen as a kind of self-analysis, into which Tót incorporates elements of his own early painting and later conceptual art, but ultimately the works are inconsistent with the oeuvre as a whole. It is as if the ecstatic, unconscious process of creation had allowed certain suppressed thoughts, or all the energies that he had buried at the end of his praxis as a painter, to emerge.

In the early 1980s in Cologne, Endre Tót was confronted with a radically new situation, the return of painting with elemental force, marked by exhibitions such as A New Spirit in Painting, Zeitgeist and Contemporary Italian Artists,[1] which he visited himself. The elemental “hunger for pictures”[2] that replaced conceptual tendencies also affected and confounded Endre Tót. The “regressive” character[3]of the expressive, figurative paintings must have seemed both repulsive and attractive. This was particularly pronounced in the German art of the period. The emergence of a new generation of artists marked a turn in painting, which must have been linked in many respects to some antecedents– such as Karl Horst Hödicke, Georg Baselitz, Markus Lüpertz, Jörg Immendorff and Sigmar Polke, or to the tradition of German Expressionism – if we take into consideration such artists as Rainer Fetting, Helmut Middendorf and Salomé on the Berlin scene, and Martin Kippenberger, Albert Oehlen, Markus Oehlen, Werner Büttner and Georg Herold on the Hamburg scene.[4] Endre Tót had a first-hand experience of this turn on the Cologne scene, keeping track of the emergence of the artists of Mülheimer Freiheit, for instance Walter Dahn, Volker Tannert, Jiří Georg Dokoupil, Hans Peter Adamski, Peter Bömmels and Andreas Schulze. Their elemental, instinctive, sometimes primitive, grotesque, sometimes highly sexual, sometimes depraved “bad painting” forced Tót to reassess a number of questions in regard to his very own turn of 1971.

[1]A New Spirit in Painting, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 15 January 1981 – 18 March 1981 (curators: Christos M. Joachimides, Norman Rosenthal, Nicholas Serota); Zeitgeist, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, 15 October - 19 December 1982.; Contemporary Italian Artists, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Museum Folkwang Essen, Kunsthalle Basel, 1980

[2]Cf. Wolfgang Max Faust – Gerd de Vries: Hunger nach Bildern. Deutsche Malerei der Gegenwart, DuMont Verlag, Cologne, 1982

[3] Benjamin Buchloh: Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression. Notes on the Return of Representation in European Painting, October, Vol. 16., Spring 1981, 39–68.

[4] In detail about this, cf.: Die 80er. Figurative Malerei in der BRD, Martin Engler Hrsg., kat. Städel Museum, Frankfurt a.M., Hatje Cantz, Ostfiledern, 2015

As he had done in the sixties, he began, in the solitude of his locked room, to pour forth a profusion of figurative paintings that questioned his conceptual period and his statement “I'm Fed Up with Painting”, and that, from a technical point of view, only remotely resembled his expressive works of the early sixties. Perhaps his Portrait of Tamás Hencze (1966) and Figurative Painting (Mrs. Tamás Hencze) (1966), which are also evocative of Willem de Kooning’s abstract expressionism, can be seen as direct precursors to the new paintings. In these works, unfamiliar, grotesque, almost caricature-like heads and figures sometimes reminiscent of tribal art (even of some works by Jean-Michel Basquiat) return again and again as exercises of ritualized painterly gymnastics. Enigmatic motifs keep recurring in the works: the mouths that open at once menacingly and sensually, the hands in body orifices and the pronounced genitalia suggest an almost provoking sexuality (endowing the phrase I’m glad if... with new meaning), and the compositions operating with motifs that evoke sacral iconography (such as constellations resembling crucifixion or coronation with a crown of thorns) are extremely disconcerting. The inscriptions and grotesque heads are perhaps stylistically closest to Walter Dahn’s paintings, and the open mouths are also reminiscent of the vomiting figures of Dahn and Dokoupil. In Tót’s case, however, the flux of images seems to allow the resurfacing of painterly gestures and motifs, buried and forgotten since the 1960s, along with the almost sexual instincts attached to them. The paint fills and sullies the whole of the picture surface again, as it did in so many of Tót’s paintings of the 1960s.

The works created between 1982 and 1985 show not only the alleged period of “Duchamp-pause”, but also Endre Tót’s entire oeuvre in a new light. Tót followed a similar path in the 1980s as he had two decades earlier: he created paintings of eruptive force, which he then renounced, as it were, arriving at a conceptual metapainting that occasionally employed the devices of painting, but which nevertheless fundamentally questioned the traditions of painting. The series of Layout Paintings, then Absent Pictures and Blackout Paintings overwrite and question the artist’s “new expressive” paintings, kept secret and hidden for decades, in the same way that the works of the 1970s renounced the artist’s early painting. As though the disconcerting “wild” paintings were associated with both suppression and shame. This is perhaps related not to the subversive sexual-corporeal content of the works (since in Endre Tót’s oeuvre these motifs usually recur in different contexts, for example in his sometimes obscene murals [“I'm glad my grandma could not see this drawing of mine”] or his series Erotic Pictures [1997-2000]), but rather to the unvarnished exposure of the instinctual sphere.

In the nineties, a prominent group of works in Endre Tót’s oeuvre were the Absent Pictures, which sometimes made deleted press images (censored), and sometimes confronted iconic works from the history of painting with their own absence. Endre Tót removes, eliminates (and thereby activates the recipient’s gaze). In contrast to the alienated-eliminated works of the seventies and nineties, Tót’s expressive paintings can be described as ‘present pictures’: direct and instinctive, instead of distancing, they bring us close, sometimes in a way that is disturbing and disconcerting. Endre Tót’s ‘absent painting’ is complementary to his ‘present painting’, and in this sense one cannot be understood without the other. Endre Tót’s oeuvre can be described as a series of shifts in perspective and a kind of fluctuation between faith in painting and doubt about it, with the necessarily unfulfillable desire for painting sometimes the driving force and sometimes the negative subject of his oeuvre. Endre Tót is concerned not only with the emptying of painting, but also with the sublimation of emptiness into painting, although he has remained silent about the most radical examples of this for decades.

When, in 1999, in the context of the Blackout Paintings, Tót alluded to the fact that he had kept something hidden, he associated the black fields with suppressed, silenced content, allowing the recipient to associate both to his silence about and to his silencing of painting and painterliness, as if his own silenced painting were hidden beneath the blacks. Endre Tót also hid his works of the early eighties in the physical sense, and systematically erased them (zeroed them out) from the narrative of his oeuvre, like the illegible (censored) words beneath the black stripes that populate his various works.[1] By revealing and presenting the hitherto hidden works, he has also given room for new interpretations of the oeuvre, revealing the hitherto concealed (unconscious) dimension of his art. He presents works that have been kept secret, but which, once visible, lose none of their mystery.

[1]Let us recall the 1979 action at Galerie René Block in Berlin entitled I'm Glad if I Can Erase One Sentence after Another, or works such as Népszabadság I. from 1993, or we can also associate the blacked-out, deleted lines of the book Örülök, ha egyik mondatot a másik után írhatom [I Am Glad if I Can Write One Sentence after Another].

Dávid Fehér

Before the closing of the Warum male ich? exhibition, Miklós Borsik analyzed Tót's painting cycle in his essay published on Artportal.hu.

Just because painting is chasing you, you are not safe. This paraphrase could be used to describe the situation that Endre Tót recalls from the 80s, in Cologne, where he hid his paintings from that time. ‘Just because you are paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.’ (Joseph Heller/Nirvana). It is not a misunderstanding to talk about paranoia in relation to Tót's pictures either. In the publication accompanying acb Gallery’s exhibition Warum male ich?, the artist reports that his previous formal language from the 60s threatened him, even though he parted with it in the golden age of his conceptualism in the 70s. This was followed by a creative phase in which Tót’s painting was not only haunted, but represented itself as a haunting. This character is reinforced by the fact that the pictures in the gallery are located in legionary proximity to each other on the wall, from which they are attacking the viewer, or at least confrontative."

We recommend Artportal’s article (in Hungarian).

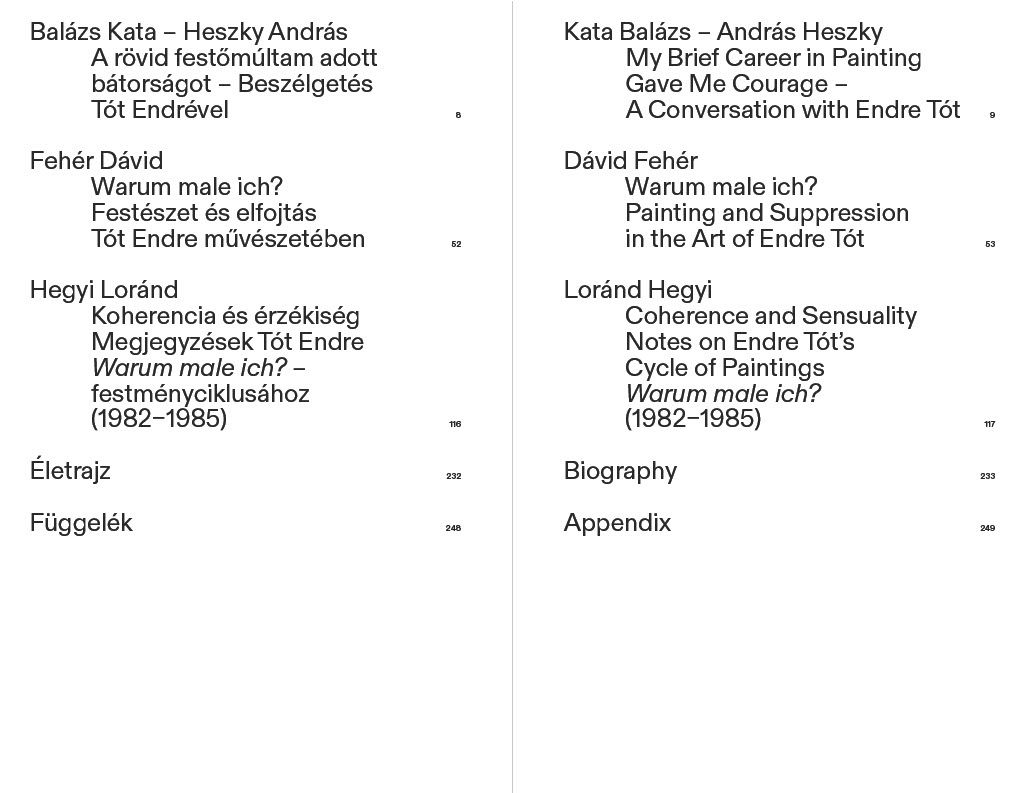

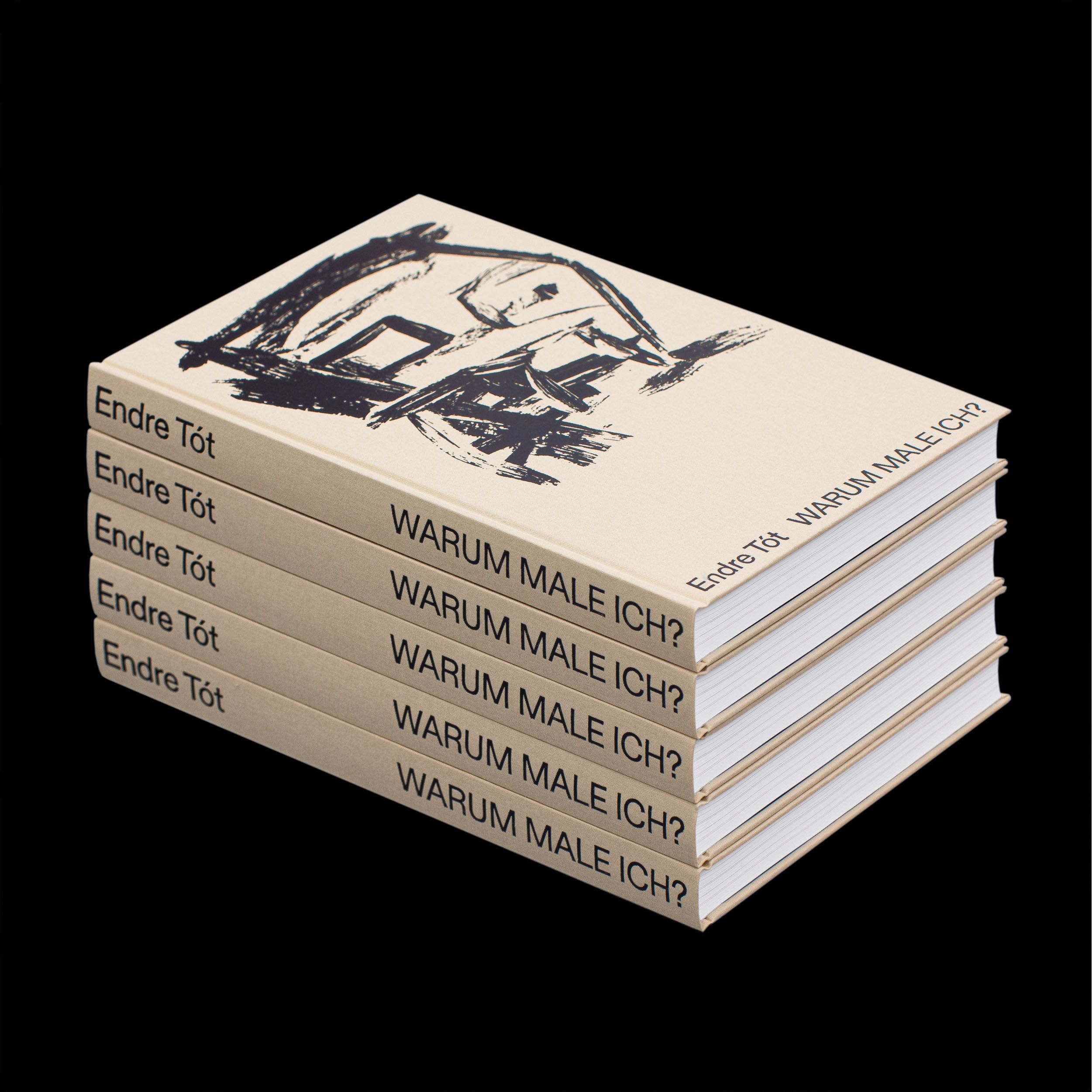

Title: Endre Tót: WARUM MALE ICH?

Published by: acb ResearchLab

Year: 2022

ISBN: 978-616-6464-00-2

Pages: 286

Edited by: Kata Balázs, András Heszky

Texts by: Dávid Dehér, Loránd Hegyi

Interview by: Kata Balázs, András Heszky

Graphic design by: Dániel Kozma

Language: Hungarian/English

Translation: Dániel Sipos

Executive publisher: Gábor Pados

Printed by: EPC Nyomda

Price: 15000 HUF, 45 EUR

acb Gallery published 100 hardbound, editioned copies of the book prepared for Endre Tót's exhibition of art historical relevance. Each of the volumes contains a unique, signed, diary-like drawing by Endre Tót, created at the same time as the Warum male ich? cycle, mainly during travels. Inquiries about the book are welcome via Editions or via our central e-mail address, while the paperback edition can be ordered via Publications.

Selected works

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic, pencil on paper

99.5 × 132 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1985

acrylic on paper

112.5 × 149 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

127 × 86 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982

acrylic on paper

104 × 111 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1983

acrylic on paper

102 × 109 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

felt tip pen and stamp on paper

28.1 × 10.2 cm

Info & Inquire

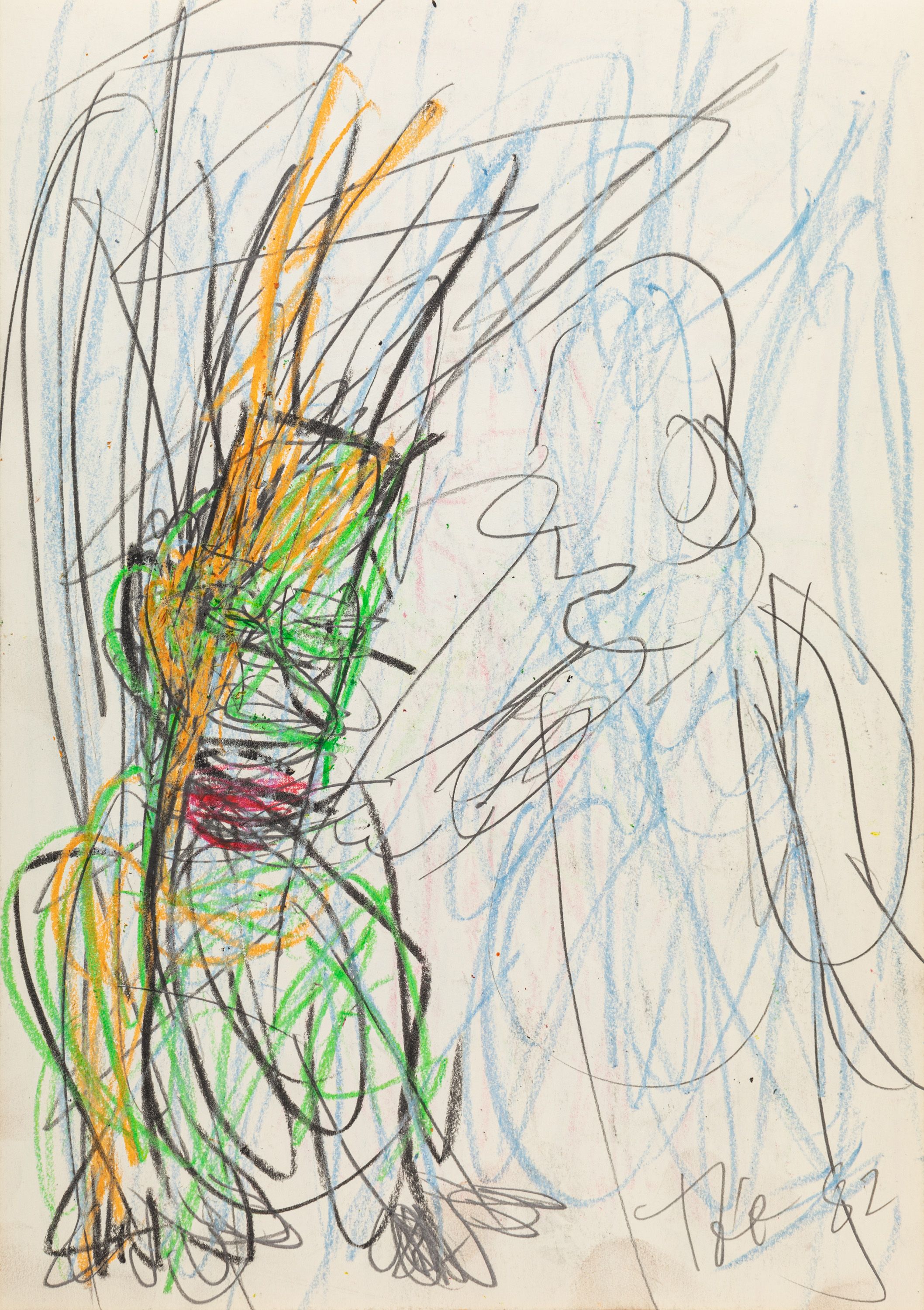

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982

colour pencil on paper

29.7 × 20.9 cm

Info & Inquire

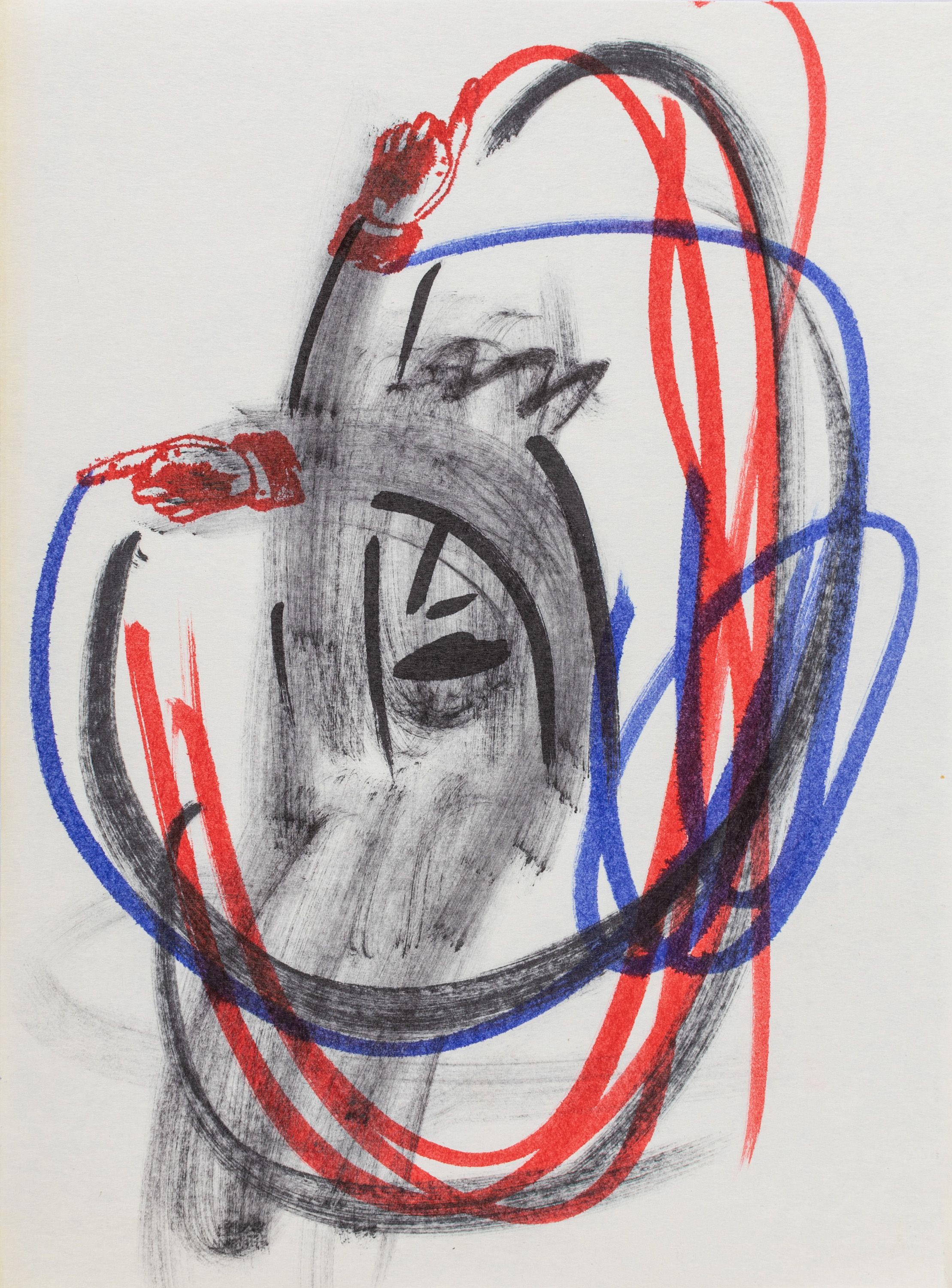

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

64.5 × 51 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

110 × 178 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

109 × 99.5 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

120 × 100 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1985

acrylic on paper

118.5 × 99.5 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

felt tip pen and stamp on paper

20.5 × 14.5 cm

Inquire

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

felt tip pen and stamp on paper

21 × 28.5 cm

Inquire

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

felt tip pen and stamp on paper

21 × 14.8 cm

Info & Inquire

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

felt tip pen, ink, pencil on paper

11.5 × 17 cm

Info & Inquire

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

felt tip pen and stamp on paper

21 × 14.8 cm

Inquire

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

135.5 × 99 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

197 × 150 cm

Endre Tót

Untitled, 1982-85

acrylic on paper

104 × 102.5 cm