János Kósa

Golden Age

| Venue: | acb Gallery |

| Date: | Oct 16 – Nov 14, 2003 |

Description

"So: one has to struggle with painting"

At the exhibition at acb we can see the works Kósa János created in the latter part of the 1990s and early 2000s. These pictures are characterized by the following features: they are painted in oil on canvas, they are representational works that create the illusion of coherent space by employing perspective that took shape in the mature renaissance. Kósa uses techniques from the past of art to paint genres and compositions typical of the given era. His works mostly resemble pictures from the 16th century and those from the 19th century before Monet. His painting methods bear a contradictory relationship with the topics that he represents, as he paints 20th-century objects with techniques of earlier eras. These works can be interpreted from the point of view of the theory of either neo-classicism or post-conceptual painting, and a third aspect may also be added: Hungarian art in the '90s, this being the instant context of the works.

These pictures here have been created based on an artistic concept whose shaping Kósa has been working on since the beginning of the decade. The result of long experimenting work manifests itself in these pictures. Kósa's activity in the '90s is defined by the analysis of contemporary art on one hand, and - parallel with the analysis - the experiment to create his own artistic identity on the other.

During his college years, Hungarian art was dominated by "neo-sensibility". Students of painting younger than him tended to give up painting after finishing their studies. They are the representatives of a new wave of installation and video art at the turn of the eighties and the nineties, e.g. Komoróczky Tamás, Szarka Péter (who, along with Ádám Zoltán, who also belongs here from this aspect, were the members of Újlak Group), Nemes Csaba, Veress Zsolt, Kiss Péter. Most of them went on to use photos, films, and digital pictures in the first part of the decade. All of them participated in major media art exhibitions (Sub Voce, The Butterfly Effect, Media Model) and also in a new wave of painting which started in the latter part of the decade (Anthology).

Kósa also started intensive media research, but apart from a short period of installations, he remained in the field of painting. He endeavored to rephrase the possibilities in painting for himself while drawing general conclusions. During this period - a time when the theory of post-modern art was becoming established and much discussed in Hungary - he kept an eye on the development of modern art, first of all, Malevich, as the ultimate painter, and artists following Duchamp and sticking to his understanding of art, e.g. Joseph Kosuth, Joseph Beuys, and Stewart Home. "I had learned from J. Kosuth that announcements or direct statements in the painting are void, and traditional painting had lost ground. At the same time, I also had the dreams of a classic painter about shapes, spaces, traditional qualities." Kósa draws the conclusion from the art of the great predecessors and uses these conclusions to define his own concept of art.

"As soon as the rules of the game called art had been changed in Florence one day to include the requirement of progress and that of solving problems, no other artistic concept had a real chance any longer," writes E.H. Gombrich in his essay, The Renaissance Conception of Artistic Progress And its Consequences Kósa is first of all interested in the authority of the creator and the originality of the work of art. "I bumped into the question of plagiarism when I had to face the basic problems of contemporary painting. As an art student, I was struggling with avant-garde those days." In his "plagiarism period" which filled up the first part of the decade Kósa repainted paradigmatic works of Cezanne, Duchamp, Picasso, and Beuys. While recreating, Kósa restudied and relived the different periods of art (e.g. with the repainting of Picasso's La Vita). Having acquired the technique and the artistic concept of the given artists, Kósa brilliantly parodied them as well. For instance, he painted a Picasso paraphrase, The Death of Painting - reminiscent of the artist's blue period - which he signed as Picasso but which he dated 1993. The reversing of I for You (Tu'm) is a Duchamp paraphrase, which Kósa - similarly to his predecessor - got a sign-painter to create for him. These works are characterized by an analytic attitude, the uncertainty of the creator's authority, the search for the identity and the social roots of the artist and art, the individuum, the demand to define what is personal and what is public, and the analysis of representation. Just as it is common in the case of contemporary mainstream, the theoretic environment greatly affects the creation of the works, which reflect the contemporary concept. The effect of the local and universal theoretic environment greatly influences the era in the form of allusions to references. One can recognize the influence of the works of Duchamp, Beuys, Andy Warhol or Kosuth, and the writings analyzing these. "At the same time I was sure I was only interested in painting, and if I take a detour to other forms of art I will only trying to find the answers to questions in connection with painting." The practice and texts of Stewart Home, and also the essays by Perneczky interpreting these, play a significant role in the artist's work as well.

In his plagiarism period, Kósa went along the way of modern art and actually reached the end. As a result of the research, the emphasis is no longer on meticulous reproduction but on creation. The praxis of painting remains and an individual style is formed, characterized by the conservation of classical painting, the graphical modus, and a particular iconography. Therefore historically Kósa's art is post-conceptual painting. His pictures are created in the styles of artistic periods which are characterized by perspective as an artistic paradigm. He adopts the representational technique and the compositional principle from these periods (especially from 16th-century painting). In the following, the term classical will be used in this sense. His style is also determined by elements - products of 20th-century high-tech - that do not fit into the composition of the pictures, which undoubtedly refer to the past. This means eclecticism of both theme and representation.

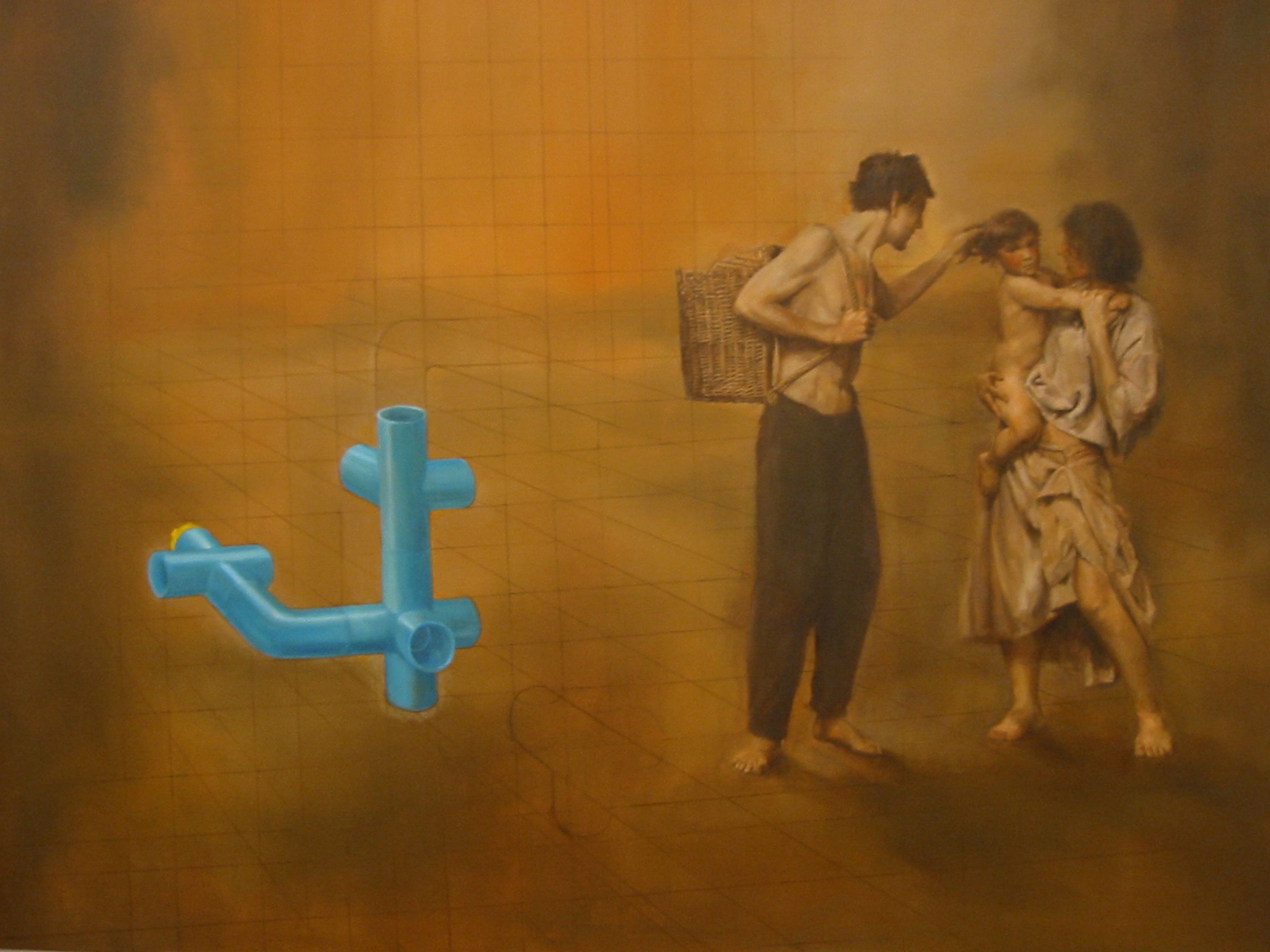

In the picture painted according to the classical modus, a high-tech instrument appears which, as we learn from the title (Restorer Robot), is restoring the ceiling of the Sixtine Chapel. In this case, the robot is the coherent part of the represented space and an example of thematic eclecticism. Elsewhere the representational technique is eclectic: Kósa uses two different techniques simultaneously (A Dame, Hackers, Infravek). Keeping the coherence of representing the space, he shows some objects as masses and assigns the place of others in the space with a network - or grid - of thin lines. This network reveals the traditional method of creating perspective, and at the same time is similar to the virtual space of digital three-dimensional (3D) modeling. The network makes it possible to see the method of the production of a picture creating the illusion of 3D space, namely the traditional (constructed with compasses and rulers) and high-tech (operated with computer software) versions thereof.

The joint use of classic and virtual space makes the components symbolical: the classic represents the past, and the digital does the present. The ideal landscape with the spaceship or the robots appearing in it has a similar role (Robot Collecting Specimen Rock in Ideal Landscape, Landing in Ideal Landscape - in the background Bacchus marches by with his escort). Their melting together, their representation in the integrated space and time means the unification of past and present, the intentional mingle of times. Due to all this, the most important references to these pictures are science-fiction (especially sci-fi films like Stanley Kubrick's 2001. A Space Odyssey, Tarkovsky's Stalker, and Matrix by the Wachowski brothers), cultural-philosophical crime stories denying the linearity of time (like Further Denial of Time by J.L. Borges), conspiracy theories (like U. Eco's parody, The Foucault Pendulum), or even the fiction of the meeting of the living past and present (like S. Spielberg's Indiana Jones trilogy). The Emperor is working with a computer placed on antique furniture, the Conspirators appear in 3D space which marks out the fasciae of a classic building. The mysterious figure that manifests itself could be a robot, a dead body that had been raised, an alien from another planet, an Übermensch, or even a human being created by an alchemist. A few of Kósa's graphics undoubtedly deal with the topic of alchemy (Alchemy) or refer to conspiracy theories (A Group Heading for the Secret Annual Meeting of the Mandelbrot Society).

At the same time, each picture has a reference to the history of art. A View of the Valley reminds us of the people looking down from C.D. Friedrich's chalk cliffs, A Visit to the Studio of a popular 19th-century style, Figure Watching a Masterpiece of the pyramid well-known from textbooks on perspective, Restorer Robot of the interest in antique ruins in the 18th and 19th centuries and Varnishing-Day with Death calls forth openings of exhibitions. Pictorial narration depicts imaginary scenes created by the artist's fantasy. The frame of the panel picture becomes the clipping of a scene from the stage or the screen. But it is also similar to the surrealistic world of Chirico, Salvador Dali, Max Ernst or René Magritte. It has been shown that the representational and thematic heterogeneity adds symbolic meaning to the elements of the pictures, which represent past, present, or future, or the mingling thereof. The multiplicity of the representational Modi has a montage-like effect, not unlike that of three-dimensional imaging. Thus these montages are related to the history of art and culture.

The triviality of the radical eclectics of the post-modern concept of art, the utilization of art's past like that of an abundant goldmine, seems to apply to Kósa as well. The main question is what the character of this concept is like. Is it revealing and liberating like in the case of a new sensibility, which is a "way out of avant-garde", or the melancholy that cultural pessimism results in?

The two figures in Hackers remind us of John the Baptist and the young Jesus or St. Sebastian. They are surfing on the internet in front of the bookshelves of a strange world. How did they get there? Where do they belong? The fact that they are working with the computer with ease suggests that they are familiar with the net. Their clothing may not only recall biblical times: they may have emerged from a negative utopia. They do not belong to a certain period, therefore their presence is universal. They know how to travel through space and time. The computer on the desk is the tool of their alchemy: they may work on altering the space-time continuum by candlelight. Prehistoric and post-historic figures for whom high-tech is a natural environment. This is true the other way around as well: the robot with its artificial intelligence is able to restore the art of humanity's past. The two rovers in Restorer Robot are arriving at the ruins of the golden age - this suggests history's being tragic. The fragments of the peaks of human creativity are taken care of by technology, which surpasses human abilities and artistic performance.

The iconographic schemes developed by Kósa unfold ideas that interpret culture or art. Media technology has created and is continually creating a culture in which "traditional values of painting" represent traditional human values in Kósa's art. Therefore his painting is not only a contribution to the conceptual questions of art but also melancholic research in the theory of culture.

Text by János Szoboszlai

(The source of texts quoted from Kósa: Kósa, J. Letter to Szoboszlai János. Balkon. 1996/4-5. pp. 37-38.)